Washing Machines and China Trade Policy

Washing machines are a big deal. Clothes get dirty and require washing. Around the world, women wash clothes and most wash by hand since they lack access to electricity, or to enough electricity to power a washing machine.

Access to modern washing machines, like access to the modern automobiles, matters in developed countries as well as poor countries. Protectionist policies that tax foreign goods may protect some jobs and some companies, but at the same time these taxes on imports reduce consumer choice and reduce innovation and dynamism across domestic companies.

Tariffs today on foreign cars and washing machines will over time reduce the competitiveness, profits, and employment of U.S. firms. So Whirlpool’s dumping charges against Korean/Chinese washing machines will hurt Whirlpool owners and employees in the years to come as well as hurting U.S. consumers now. (Article here and more on Asian washing machine protectionism below.)

Virginia Postrel’s 2001 New York Times column, “Economic Scene: Wealth Depends on How Open Nations Are to Trade,” quotes from economists Stephen L. Parente and Edward C. Prescott’s book Barriers to Riches in explaining how protectionist policies allowed decades of stagnation across India:

Virginia Postrel’s 2001 New York Times column, “Economic Scene: Wealth Depends on How Open Nations Are to Trade,” quotes from economists Stephen L. Parente and Edward C. Prescott’s book Barriers to Riches in explaining how protectionist policies allowed decades of stagnation across India:

In other words, says Professor Parente, “poor countries are poor because some groups are benefiting by the status quo,” and those groups use the law to block change. India has a long history of this. In the early 20th century, strikes kept Indian textile mills from increasing the number of looms each worker operated, and the government protected the old ways through steep tariffs on foreign textiles. As a result, from 1920 to 1938 textile productivity rose by only a third as much in India as it did in Japan, which was beginning its climb to prosperity.

Other Indian government protectionist policies blocked imports of Japanese and other foreign cars, and blocked foreign direct investment. Special interests limited competition within India (blocking new firms). These established companies, working with labor unions and government, blocked imports of foreign manufactured goods. So India protected existing firms and jobs and stayed poor through the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, and only started prospering as barriers to international trade and foreign direct investment were lifted in the early 1990s.

Here is a three-minute video from The Commanding Heights documentary on India’s Permit Raj, and the stagnation of India’s protected Ambassador car company vs. Japan’s Toyota:

This is a lesson citizens in the U.S. should learn. Domestic regulations coupled with protectionist policies can slow and even stop advances across whole industries. Plus protectionism is often advanced under the guise of various policies claimed to be pro-consumer, antitrust, environmental, and pro-labor.

More on this below, but first a brief look at the global significance of washing machines, and the dangers of expanding environmental and labor regulation in future Asia trade policies.

[Remember that China is both a developed and an undeveloped country, sort of like Europe after the fall of communism. When Deng Xiaoping’s reforms began in 1978, parts of China were already market-based (Taiwan and Hong Kong). Agricultural reforms allowed farm families private property, which immediately and dramatically increased food production. Reforms opened a handful of southern and coastal regions to foreign investment, and by far the biggest early investors where Chinese entrepreneurs who had earlier fled China and prosper in other countries. By the 1990s these free-enterprise zones had surged ahead, with 40% annual growth rates in some cities. By 2015 hundreds of millions in China have enjoyed 25 to 35 years of rapid and sustained economic development. Rural regions have been slower to enjoy the gains from economic liberalization.]

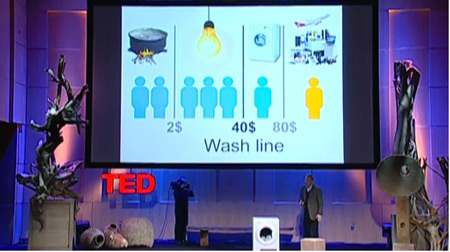

Swedish statistician Hans Rosling explains the magic of washing machines in his famous TED talk (now with over 2 million views):

Washing machines, or the lack of them, impact every family on the planet. Rosling is passionate in advocating access to electricity and washing machines for Earth’s five billion people still living below the “wash line.” Rosling says one billion live above the “airline,” with access to all sorts of other machines and gadgets and even flying machines. Another billion can’t afford all that, but do have electricity and washing machines. But below the wash line, five billion live in families where women take dirty clothes to the river each week, bring water from wells, or, for those lucky enough to have running water, wash clothes by hand at home.

My mother had a washboard in the utility room before we had any machines for cleaning. We later bought a washing machine and mom hung clothes out to dry in the patio or front yard (depending on rain). Later we bought a dryer and still later a dishwasher. These magic appliances made daily chores much, much easier.

My mother had a washboard in the utility room before we had any machines for cleaning. We later bought a washing machine and mom hung clothes out to dry in the patio or front yard (depending on rain). Later we bought a dryer and still later a dishwasher. These magic appliances made daily chores much, much easier.

There are important ways this washing machine progress story connects to the Stoa league’s Asia trade topic. Central to Hans Rosling’s TED presentation: Western environmentalists believe Earth’s ecosystems unable to cope with the economic expansion and surge in electricity use necessary to power washing machines for the billions still washing clothes by hand. Rosling mentions his environmentally-conscious Swedish students who ride bicycles each day thinking to reduce their “carbon footprint.” He asks for a show of hands on bicycles first, then on clothes washing. None of his students wash their clothes by hand.

U.S. trade policy with China, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea turns on environmental theories and policies involving energy use and global climate change (as well as separate labor, antitrust, and other policies).

Environmentalists want more “green” energy used in China, and find common cause for protectionist policies that would also aid more energy-efficient U.S. manufacturers. Chinese manufacturers naturally shift to more efficient and less polluting power from natural gas (as they have in the more developed southern and coastal provinces). The Chinese government, on the other hand, is spending billions on heavily-subsidized “green” solar and wind power installations, and spending billions more subsidizing heavily-polluting coal-powered steel production at money-losing state-owned industries. These costly policies are driven by politics. Job-loss fears and corruption sustain coal and steel subsidies, and fear of foreign environmentalists and protectionism, plus corruption, sustain solar and wind power subsidies.

Unless the Chinese government makes a big show of “investing” billions in solar and wind power, being a leader in green energy, they risk U.S. and E.U. environmentalists joining with manufacturing and labor interests to push for more protectionism. This 2011 article, “Prospects for Green Protectionism under China-US Energy Cooperation” discusses this dynamic:

A typical example was that the US threatened to impose unilateral trade sanctions, especially the so-called “carbon tariffs”, on energy-intensive products imported from those developing countries that would not adopt CO2 mitigation policies “comparable” to that of the US. The Waxman-Markley bill, passed in June 2009 by the US House of Representatives, and most other proposed [laws/legislation] in recent years all contained such provisions, [with/regarding] China as the major target.

The Chinese government understands the threat of “carbon taxes” so continues to subsidize solar and wind power generation (similar to subsidies by U.S. and European governments).

Separate from green energy policies are more traditional protectionist policies claiming foreign firms are hurting the U.S. by selling manufactured goods below cost. One example are recent efforts by Whirlpool to slap tariffs on Korean washing machines made in China. Courthouse New Service has this December 30, 2015 story, “Whirlpool Wants Tariffs for Chinese Washers.”

Appliances maker Whirlpool wants the federal government to impose tariffs on imported Samsung and LG washing machines made in China, claiming they are priced too low. Whirlpool Corp. filed an anti-dumping petition with the U.S. Department of Commerce and the U.S. International Trade Commission, accusing its Korean rivals of circumventing federal orders. Dumping refers to selling a product in the United States at a price that is lower than “the price for which it is sold in the home market,” or the fair value, according to a government handbook.

Does it seem reasonable that Samsung and LG would invest hundreds of millions in design, factories, tooling, production, and shipping to sell their new washing machines in the U.S. for less that it costs to produce them?

The popular theory is that firms engage in “predatory pricing,” with big firms selling below cost in order to drive their smaller competitors out of business. Once competitors are bankrupt or leave the business, these “predatory” firms plan to recoup their losses as monopolists by raising prices much higher.

It is an interesting theory, but according to economists, doesn’t work in practice. “Antitrust,” an article in The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, notes:

It is an interesting theory, but according to economists, doesn’t work in practice. “Antitrust,” an article in The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, notes:

Fred McChesney in his

Likewise, belief in the efficacy of predatory pricing—cutting price below cost—as a monopolization device has diminished. Work begun by John McGee in the late 1950s (also an outgrowth of the Chicago Antitrust Project) showed that firms are highly unlikely to use predatory pricing to create monopoly. That work is reflected in several recent Supreme Court opinions, such as that in Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp., where the Court wrote, “There is a consensus among commentators that predatory pricing schemes are rarely tried, and even more rarely successful.”

“This is the best story in the world today.”

As Stoa debaters research Asia trade policy they should always ask themselves: who benefits from current and proposed trade policies? The first post on this debate topic last June, “Most Trade Policy is Driven by Special Interest Groups,” emphasized that government regulations are usually proposed and promoted by concentrated interest groups that expect to benefit from anti-dumping policies and other trade restrictions.

Trade policy is not so different from other regulations. Regulations restricting ride-sharing, for example, are passed in the name of protecting the public but actually to protect established taxi and limousine companies from competition.

Everyday people benefit from wider transportation options, but not enough to lobby, protest, or vote because of this single issue. Taxi companies and drivers are concentrated and motivated, and they will lobby and protest to defend their government-protected privileges, just as Whirlpool and worker unions do to try to raise costs for Korean/Chinese companies.

Relatively open trade with China was originally easy because in the 1980s China was so poor and rural that manufacturing there was little threat to U.S. firms. As China under Deng Xiaoping opened up parts of the economy to foreign direct investment, manufacturing boomed. The Chinese economy integrated with the U.S., South Korean, Japanese, and Taiwanese economies. Now hundreds of millions of jobs across these five economies are woven together through tens of thousands of interconnected companies, supplier contracts, and distribution agreements.

The results of this relatively open trade and investment policy over three plus decades has been lower costs for goods for world consumers and astonishingly good news for hundreds of millions across China. A Huffington Post article, Global Poverty Will Hit New Low This Year, World Bank Says, reports the amazing story that as world population grew by billions since 1990, extreme world fell:

…a stunning decline from the numbers reported over the last 25 years. According to the World Bank, 37.1 percent of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty in 1990. In 2015, that number is estimated to drop to 9.6 percent.

In an October 7, 2015 Cato at Liberty post, “The Dramatic Decline in World Poverty,” Ian Vasquez connects this poverty reduction with the expansion in economic freedom, especially in China:

The drop in poverty also coincides with a significant increase in global economic freedom, beginning with China’s reforms some 35 years ago and the globalization that followed the collapse of central planning in the late 1980s and early 1990s. As we celebrate this achievement and strive for further progress, we should not lose sight of the central role that voluntary exchange, freedom of choice, competition and protection of property play in ending privation.

Open U.S./China/Japan/SK/Taiwan trade policy has been the major factor reducing world poverty (India helped too, after opening to international trade and investment in the 1990s).