U.S. Policies for Prosperity from the World’s Oceans

Oceans are a lot like land, just wetter. Wet is good for life, and the world’s oceans covering 70% of the planet can be a source of vast new wealth or conflicts. A May, 8, 2014 Wall Street Journal op-ed noted that “West Africa loses about $1.3 billion to illegal fishing.” (How Africa Can Capitalize on Its Progress). On the east of Africa, illegal offshore fishing launched Somalian pirates. More recent articles claim increase security has frustrated Somalian pirates and led many to turn instead to providing security for illegal fishing. A U.N. Monitoring Group report claims:

Oceans are a lot like land, just wetter. Wet is good for life, and the world’s oceans covering 70% of the planet can be a source of vast new wealth or conflicts. A May, 8, 2014 Wall Street Journal op-ed noted that “West Africa loses about $1.3 billion to illegal fishing.” (How Africa Can Capitalize on Its Progress). On the east of Africa, illegal offshore fishing launched Somalian pirates. More recent articles claim increase security has frustrated Somalian pirates and led many to turn instead to providing security for illegal fishing. A U.N. Monitoring Group report claims:

The security services for fishermen bring piracy full circle. Somali pirate attacks were originally a defensive response to illegal fishing and toxic waste dumping off Somalia’s coast. Attacks later evolved into a clan-based, ransom-driven business.

Up to 180 illegal Iranian and 300 illegal Yemeni vessels are fishing Puntland waters, as well as a small number of Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean and European-owned vessels, according to estimates by officials in the northern Somali region of Puntland. International naval officials corroborate the prevalence of Iranian and Yemeni vessels, the U.N. report said.

Fishermen in Puntland “have confirmed that the private security teams on board such vessels are normally provided from pools of demobilized Somali pirates and coordinated by a ring of pirate leaders and associated businessmen operating in Puntland, Somaliland, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Oman, Yemen and Iran,” the report said.

Communal ownership and government management of land has long been a source of poor incentives, mismanagement, and famine. Why would people believe that government management of ocean waters be any less productive?

Dogs Bark; Dogfish Don’t

On land, dogs helped with private land ownership. Prehistoric hunters and gatherers owned dogs that helped protect property and belongings while owners were off hunting for food. Over centuries, private ownership of property encouraged investment, increasing knowhow and boosted productivity. Hernando de Soto tells of informal land ownership where communities informally agree who owns what. Dogs bark to let people know when they are approaching someone’s private property. (Though dogs also bark when hungry, confused, lonely, irritated, or just because. Thus in America people have property titles as well as dogs.)

Hernando de Soto’s theory of the barking dog suggested that wherever there is a barking dog… there is a household. And a household in Peru or Cairo that could be conferred with leasehold – and thereby, legitimized and enabling its inhabitants to step in from the grey shadows to formal legal recognition. [Source.]

Globalization at the Crossroads, a documentary on Hernando de Sotos’ research, is available online.

It’s harder to identify ownership boundaries offshore. Land boundaries can be shown with stakes, chalk, fences, trees or barking dogs. Out in the ocean, who has title and where are the property lines? Technology offers various solutions.

Football fans used to puzzle over just where the first down line was. Markers along the sidelines were of limited help locating midfield first downs. Now on televisions bright yellow lines show the first down line. Computers digitally draw a line between the sideline markers.

Computers, GPS devices, and satellite data could draw property lines onto the ocean to identify who owns or is responsible for stewardship of fisheries regions. Developing and identifying clear and enforceable property boundaries for fisheries isn’t free but neither was establishing property rights on land.

Through history governments have’t been the source of law (though have been the source of much regulation). Common fisheries practices and traditions develop and enforce ocean property rules and rights. (Though governments often jump in with top-down regulations.) As on land, property institutions develop before government, and government is considered just to the extent it supports pre-existing norms and rules. (See Richard Pipes’ Property and Freedom for discussion.)

As an example, consider the Netflix reality show Battlefish, sharing  the experiences of open ocean tuna fishing boats off the Oregon coast. Captains (including my cousin’s son, Bill Rehmke) search the seas for signs of tuna. When captains identify a likely area they fish along a rectangular pattern (discussed in an early Battlefish episode) that establishes their tuna fishing territory. Other boats have to find their own, often nearby, tuna territory. (Of course lots of state and federal regulations are on the books for tuna and other commercial fisheries.)

the experiences of open ocean tuna fishing boats off the Oregon coast. Captains (including my cousin’s son, Bill Rehmke) search the seas for signs of tuna. When captains identify a likely area they fish along a rectangular pattern (discussed in an early Battlefish episode) that establishes their tuna fishing territory. Other boats have to find their own, often nearby, tuna territory. (Of course lots of state and federal regulations are on the books for tuna and other commercial fisheries.)

Over time, as pressure on land and ocean resources increases, developing property rights, or other systems to manage commons to reduce over-harvesting, is key to fishery sustainability and productivity.

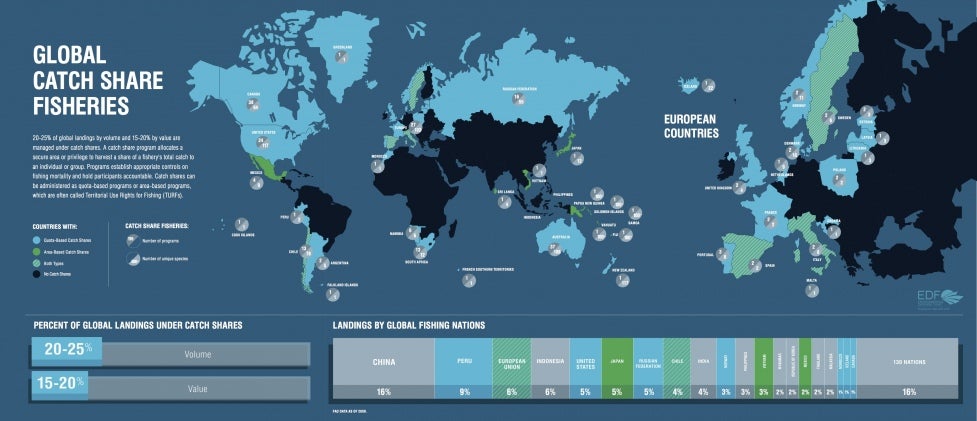

Here is Environmental Defence Fund page on catch shares.