Startup Cities or Foreign Aid for Fish, Food, and Infrastructure?

NCFCA’s 2020-21 topic on E.U. immigration reform is connected to past topics on foreign aid, transportation, agriculture, China, and ocean policy. All key topics because for mankind, prosperity follows agriculture, fisheries, transportation, and trade.

NCFCA’s 2020-21 topic on E.U. immigration reform is connected to past topics on foreign aid, transportation, agriculture, China, and ocean policy. All key topics because for mankind, prosperity follows agriculture, fisheries, transportation, and trade.

A recent NSDA (public/private school) topic on increasing legal immigration is similar to the E.U. immigration reform topic. Different places but similar dynamics, economics, and politics. Oceans allow refugees to flee poverty and chaos, but sometime perish at sea. What if oceans could be a destination rather than just a way to travel from one continent to another?

Oceans could better feed the world, improving living standards in poor countries (thus reducing out-migration pressure), with improved governance. Better governance on land helps agriculture flourish, just as aquaculture could at sea. The best foreign aid for the poor would be the gift of better governance.

And the easiest most effective ticket to better governance is just that, a simple ticket by bus, train, boat, or plane to better governed lands–all of which are far wealthier. The Frasier Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World Report provides numbers on the causal link between better governance and prosperity.

But about oceans as a refugee destination? How is that possible. Well, it’s not now, but it’s coming, perhaps soon. Can Seasteading Help in the Humanitarian Refugee Crisis? (Seasteading Institute, June 22, 2017) sketches the possibilities. Joe Quirk’s book Seasteading: How Floating Nations Will Restore the Environment, Enrich the Poor, Cure the Sick, and Liberate Humanity from Politicians (GoodReads).

…..

Economist Art Carden cites Lant Pritchett on the amazing benefits of migration compared to foreign aid for helping the poor. In Are We Serious About Reducing Poverty? Then We Need To Welcome Immigrants (Forbes, October 19, 2018), Carden also discusses The Biggest Idea in Development That No One Really Tried (Center for Economic Growth, prepared for Upton Forum at Beloit College) and Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk? (Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2011).

Foreign aid and international terrorism challenges turn on improving governance, and migration gives the world’s poor a path to better lives. Barriers to labor mobility reduce the world wealth far more that barriers to trade and investment (from JEP, 2011 article):

The gains from eliminating migration barriers dwarf—by an order of a magnitude or two—the gains from eliminating [international trade and investment] barriers…

…existing estimates suggest that even small reductions in the barriers to labor mobility bring enormous gains. In the studies of Table 1, the gains from complete elimination of migration barriers are only realized with epic movements of people—at least half the population of poor countries would need to move to rich countries. But migration need not be that large in order to bring vast gains.

Policy reforms improving labor mobility might seem limited to the NSDA legal immigration resolution. But an alternative to more people moving to countries with better governance is “moving” better governance to them. Conquest, colonialism, and imperialism were past tried and terrible versions. Voluntary (or less coercive) alternatives were charters. Charter cities expanded governance choices. Some charter cities are fairly new (Hong Kong, Singapore, Shenzhen), others are left over from Europe’s medieval past (see, for example, Rick Steve’s fun travel episode, Little Europe: Five Micro-Countries, touring Andorra, San Marino, Vatican City, Monaco, and Liechtenstein.)

Around the world, past and present, are prosperous enclaves, charter cities, free cities, and special economic zones. Hamburg in Germany has an official name from its history: “Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg.” Europe flourished for centuries from the development of cities, not nation states. This city history is told in Sebastian Mallaby’s The Politically Incorrect Guide to Ending Poverty (The Atlantic, July/August 2010). Drawing from history, Paul Romer calls for states to establish zones of better governance (“new cities with new rules”) inside their poorly governed countries (Honduras, for example):

Rather than betting that aid dollars can beat poverty, Romer is peddling a radical vision: that dysfunctional nations can kick-start their own development by creating new cities with new rules—Lübeck-style centers of progress that Romer calls “charter cities.” By building urban oases of technocratic sanity, struggling nations could attract investment and jobs; private capital would flood in and foreign aid would not be needed.

Returning to political arrangements from the middle ages doesn’t sound forward-thinking. But Mallaby transitions from Henry the Lion’s 12th Century launch of self-governing city of Lubeck to Paul Romer’s call for new charter cities:

And since Henry the Lion is not on hand to establish these new cities, Romer looks to the chief source of legitimate coercion that exists today—the governments that preside over the world’s more successful countries. To launch new charter cities, he says, poor countries should lease chunks of territory to enlightened foreign powers, which would take charge as though presiding over some imperial protectorate. Romer’s prescription is not merely neo-medieval, in other words. It is also neo-colonial.

Paul Romer’s 2009 TED talk Why the world needs charter cities now has over 600,000 views and his 2011 TED talk The world’s first charter city? has almost 500,000 views. Romer’s hoped for Honduran charter city has been delayed by politics, but also by a fear that new charter cities might be (or soon become) a new kind of colonialism.

Charter cities (and Startup Cities) can be thought of as a kind of federalism, where decentralized states develop a range of governance. Switzerland’s Cantons are a proven example of prosperity with strong rule of law and local governance. Consider What the Swiss Can Teach Us About Development (Fragile States, 2012):

International efforts to help developing countries start with a mental model of how government should be structured. It is based on the most common European model of state building—a model initially developed by France but shared by most countries today. European history did, however, have another model, one that is not well remembered but that may be much more useful for fragile states—the Swiss model.

See Unlocking Prosperity Through Charter Cities (NewCities.org, October 15, 2018) for an updated look at the potential. All three debate leagues (Stoa, NCFCA, and NSDA) have had recent China-related topics. How did China’s cities become so prosperous so quickly and why haven’t Africa’s cities followed that path?

China’s lifting of 800 million people out of poverty is the greatest humanitarian miracle of the post-war era. A combination of urbanization and special economic zones was responsible for China’s success. Shenzhen, for example, was a fishing village with 30,000 residents in 1980 when it was declared one of the country’s first special economic zones. Today, it is the manufacturing capital of the world and boasts a population of 12 million.

Unfortunately, to date, no one has figured out how to replicate the Chinese success. Much of sub-Saharan Africa, for example, experienced urbanization without industrialization. Registering a business is also out of reach for most, since doing so requires 50 percent of per capita income. It doesn’t take an economist to understand the negative impacts of such a hindrance on entrepreneurship. …

Charter Cities and Startup Cities

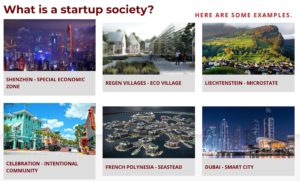

Charter Cities and Startup Cities offer related models for better governance in developing countries. The Startup Societies website offers many working and in-process examples, with the theme “Don’t Argue. Build.”

Charter Cities and Startup Cities offer related models for better governance in developing countries. The Startup Societies website offers many working and in-process examples, with the theme “Don’t Argue. Build.”

A startup society is typically a small territorial experiment in government. For centuries, innovators have created enclaves to escape institutional barriers. America itself was created to escape religious persecution in Europe. The startup societies of today are making the world into a more diverse and competitive place.

Past Economic Thinking posts have discussed charter cities as models for economic freedom, peace, and prosperity. One example: China to Palestine: Let Charter Cities & Economic Freedom Bloom.

Refugee Cities offer a related way to offer better options to the tens of millions of refugees worldwide

For all the debate topics above, a list potential federal reforms or all-new programs would be nearly endless. Yet economists make the case that these possible plans, past, current, and proposed, are more the problem than the solution.

That’s a challenge for policy debaters tasked to create and propose new legislation advancing reforms to existing programs and policies. It would seem negative or cynical to just call for abolishing failed federal programs right and left with the wave of a wand..

Economic principles can help students understand why foreign aid, immigration, and foreign policy programs restrict local enterprises where people around the world respond to local needs and opportunities.

Past policies to help farmers have hurt farmers both in the U.S. and overseas, drained taxpayer dollars and raised food prices. Similarly federal transportation policies have restricted and distorted transportation by air, sea, and land, raising costs and increasing congestion.

Affirmatives for debate topics often try to craft reforms to reduce the costs and damage of past policies, or to advance new policies. With foreign aid, students can debate benefits and harms. This LA Times article U.S. foreign aid: A waste of money or a boost to world stability? Here are the facts, (May 19, 2107) offers a review highlighting the benefits of foreign aid and popular misunderstandings.

First though, it’s worth noting that as with agriculture and transportation policies, most people who work, research, and write on these topics are natural advocates for them. The USAID website, for example, focuses on the benefits of USAID foreign aid programs, just as the Mercy Corps website presents the need for foreign aid and Mercy Corps programs to help. And USAID has a page of stories on Mercy Corps programs using USAID funds.

But apart from the challenges of improving foreign aid we have vast real world examples of billions(!) escaping poverty without foreign aid. The truth on poverty reduction around the world (The Guardian, October, 23, 2018) looks at still poor Nigeria and how it got left behind economically:

The obvious next question is “how did the rest of the world do it”. On this note, a new paper published by Lant Pritchett at the Centre for Global Development identifies some important observations. A significant part of the poverty reduction has been driven by economic growth in not just large economies like China and India but in smaller countries like Vietnam. Between 1980 and 2017, China reduced poverty from 84 percent to less than two percent today. In Vietnam, poverty dropped from 33 percent in 1993 to less than 10 percent in 2016.

Over this same period, many rich countries and development agencies have launched various programs and interventions across many countries including in Africa, trying to alleviate poverty. The verdict according to Pritchett? Economic growth and migration are responsible for almost all poverty reduction over the last four decades. Almost all countries that have reduced poverty significantly over the last few decades have experienced periods of strong economic growth. Economic growth is a necessary condition for any sustainable reduction in poverty. It does not mean that growth automatically reduces poverty, but no growth definitely implies that poverty is not going to be reduced.

Research reference: Alleviating Global Poverty: Labor Mobility, Direct Assistance, and Economic Growth (March 20, 2018)