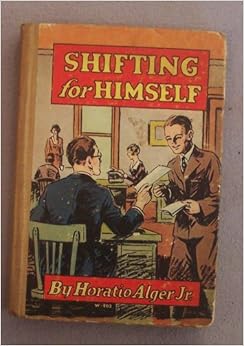

Shifting for Himself in an Earlier Great Recession

In the last three years many thousand American boys have been compelled, like Gilbert, to give up their cherished hopes, and exchange school-life for narrow means and hard work. Nothing is more uncertain than riches; and such cases are liable to occur at all times. — Horatio Alger Jr., Preface, Shifting for Himself

India and China stand out, both by virtue of their vast populations and also because their growth record in the 1980s and 1990s was so much better than the poor-country average. A population-weighted line of best fit drawn through this second chart would indeed slope downwards, implying both catch-up and narrowing inequality.

China (which has never shown any interest in MDGs) is responsible for three-quarters of the achievement. Its economy has been growing so fast that, even though inequality is rising fast, extreme poverty is disappearing. China pulled 680m people out of misery in 1981-2010, and reduced its extreme-poverty rate from 84% in 1980 to 10% now.

Stephen Davis, in a 2012 column in The Freeman, notes that the recent “Great Recession” and weak recovery since is often compared to the Great Depression of the 1930s, but shouldn’t be.

Davis writes, in “Are We Looking at the Wrong Depression?”:

Davis writes, in “Are We Looking at the Wrong Depression?”:Most of this attention is being paid to the Great Depression of the 1930s. However, it is worth pointing out the important ways in which the present situation differs from that of the 1930s. … Perhaps we are looking at the wrong “Great Depression.” …

Until as late as the 1950s, “Great Depression” in economic history generally referred to the period between 1873 and 1879 (in the United States) or 1873 and 1896 (in the United Kingdom and much of Europe). When we look more closely at those years, the likeness to where we are now becomes noticeable. The “Long Depression” (as it has come to be known) was sparked by a global financial panic in 1873, which arose from the bursting of several speculative bubbles, particularly in railroads and real estate.

Economic historians also compare and contrast the post-WWI recession of 1920-1921 to the Great Depression. Few people today know much about this recession, even though it was deep and severe because it was short and the U.S. economy recovered quickly. For more, see Robert Murphy’s 2009 Freeman article “The Depression You’ve Never Heard Of: 1920-1921.“

Economic historians also compare and contrast the post-WWI recession of 1920-1921 to the Great Depression. Few people today know much about this recession, even though it was deep and severe because it was short and the U.S. economy recovered quickly. For more, see Robert Murphy’s 2009 Freeman article “The Depression You’ve Never Heard Of: 1920-1921.““Shifting for Himself” records the experiences of a boy who, in the course of a preparation for college, suddenly finds himself reduced to poverty. He is obliged to leave his books, and give up his cherished plans. How cheerfully Gilbert Greyson accepted the situation, and settled down to regular work, what obstacles he encountered and overcame, and what degree of success he met with in the end, the reader of this story will learn.

Though it must be admitted that Gilbert was more fortunate than the majority of boys in his position, it is claimed that he displayed qualities which may wisely be imitated by all boys who are called upon to shift for themselves. In the last three years many thousand American boys have been compelled, like Gilbert, to give up their cherished hopes, and exchange school-life for narrow means and hard work. Nothing is more uncertain than riches; and such cases are liable to occur at all times. I shall be glad if the story of Gilbert Greyson and his fortunes gives heart or hope to any of my young readers who are similarly placed. The loss of wealth often develops a manly self-reliance, and in such cases it may prove a blessing in disguise.

— New York, Oct. 20, 1876.

Expanding economies open doors of opportunity which allow the enterprising to step through, learn work skills and earn, save, invest, and innovate. Because people are quite different in their natural and developed skills and energies, and because circumstances differ, earnings will naturally vary along with levels of success. How wide these differences of income shouldn’t matter as long as legal systems are tolerable and overall incomes and standards of living are rising.