Rubber Ducks Measure Ocean Currents

Who knew that “tens of millions” of rubber ducks race rivers for charity. Curtis Ebbesmeyer, in a KUOW radio interview, discusses the popular charity races where people can bet on (or “adopt”) a rubber duck for $5, and thousands are released to “race” (i.e. drift) down river.

Who knew that “tens of millions” of rubber ducks race rivers for charity. Curtis Ebbesmeyer, in a KUOW radio interview, discusses the popular charity races where people can bet on (or “adopt”) a rubber duck for $5, and thousands are released to “race” (i.e. drift) down river.

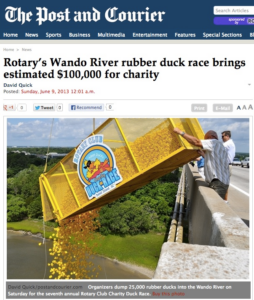

A January race of 25,000 ducks down the Wando River was expected to raise $100,000 for charities (plus $10,000 for the winning duck).

Downstream, oil booms and a “Rotary Navy” of boats and kayaks on the Wando kept stray ducks from floating away uncaptured.

Apparently a significant number of ducks do float away uncaptured, passing the finish line and escaping out to sea. Because each duck is tagged for the contest, ocean researchers can learn about ocean currents as these ducks are carried by ocean currents and breezes. Runaway rubber ducks and their value for research, is discussed in the Ebbesmeyer KUOW interview.

Ebbesmeyer tells the story of a container of 28,000 rubber ducks lost at sea when it went overboard in 1992. As many of these ducks have been recovered around the world–as far away as Scotland–researchers learn more about ocean currents:

Today that flotilla of plastic ducks are being hailed for revolutionizing our understanding of ocean currents, as well as for teaching us a thing or two about plastic pollution in the process, according to the Independent. (Source)

The quote above draws from a 2011 story in The Independent, “Lost at Sea: On the Trail of Moby Duck“. Drifting rubber ducks make for an entertaining story, but critics argue that hundreds or even thousands of other less entertaining containers are lost at sea each year, dumping their contents on the open ocean. The lost rubber ducks, according to one author:

… lays bare a largely ignored threat to the marine environment: the vast numbers of containers that fall off the world’s cargo ships.

No one knows exactly how often containers are lost at sea, due to the secretive nature of the international shipping industry.

Rubber ducks don’t seem dangerous to marine life, but eventually they break apart, as do millions of other plastic products that find their way out onto the world’s oceans. A number of books have profiled the issue and some claim giant islands of plastic debris can be seen from space.

Todd Meyer of the Washington Policy Center, in a talk to Seattle area debate students, argued that the amount and dangers of ocean plastic are exaggerated. Research with the actual numbers of ocean plastic estimates can be found on the NOAA website, and in Todd Meyer’s book Eco-Fads: How the rise of trendy environmentalism is hurting the environment.

Todd Meyer of the Washington Policy Center, in a talk to Seattle area debate students, argued that the amount and dangers of ocean plastic are exaggerated. Research with the actual numbers of ocean plastic estimates can be found on the NOAA website, and in Todd Meyer’s book Eco-Fads: How the rise of trendy environmentalism is hurting the environment.