For American Logos students: I’ve been asked to give presentations on Poverty and on Marxism. I discuss both in this post and recommend various essays and videos for further research. It makes sense to separate past and developing world poverty from modern developed economy discussions of poverty. Similarly past Marxism was discussion and debate about economics and institutions while current Marxism is more about language and claims about power.

The Western World from Poverty to Prosperity

The whole world used to be poor, apart from a tiny percentage of kings, nobles, and merchants. Now in the developed world, poverty is mostly relative. If all your neighbors are multi-millionaires who seem to own every new car, gadget, and take exotic vacations, your family may feel poor by comparison. Looking around the world and through history through, can help us realize the amazing prosperity we take for granted.

Being wealthy won’t in itself make people content or happy. If we covet the wealth or life or looks or smarts our neighbors may have, we can think life unfair and no amount of wealth holds off despair. And unless we gain control of our behavior, channel our passions, nurture our faith, family and friendships, build our character, wealth will be more a risk than reward. Surviving is still a challenge for billions around the world and has been for all time, but it’s not the only challenge human beings face.

Researching difficult public policy questions, framed as motions, is a challenge debaters accept. And the mystery of wealth, of overcoming poverty, is one that economists research, discuss, and debate. Peruvian economist Hernado de Soto is author of The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. More on DeSoto’s research and online videos below. DeSoto follows in the footsteps of a much earlier economist, Adam Smith, a moral philosopher who published in 1776, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.

Researching difficult public policy questions, framed as motions, is a challenge debaters accept. And the mystery of wealth, of overcoming poverty, is one that economists research, discuss, and debate. Peruvian economist Hernado de Soto is author of The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. More on DeSoto’s research and online videos below. DeSoto follows in the footsteps of a much earlier economist, Adam Smith, a moral philosopher who published in 1776, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.

Economists from Adam Smith forward have made the case for economic freedom and sound legal institutions as the pathway from poverty to prosperity:

…why are some countries able to take advantage of the division of labor and become rich, while others fail to do so and remain poor? Smith’s answer, in an important but neglected theme of his work, is the security of property rights that enable individuals to “secure the fruits of their own labor” and allow the division of labor to occur. Countries that can establish a “tolerable administration of justice” to secure property rights and allow investment and exchange to take place will see economic progress take place. Smith’s emphasis on a country’s “institutions” in determining its relative income has been supported by recent empirical work on economic development. ADAM SMITH’S “TOLERABLE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE” AND THE WEALTH

OF NATIONS (NBER Working Paper, Douglas Irwin,October 2014))

From Famines to Plenty, Overpopulation fears to Demographic Doom

Around the world and through the centuries, nearly all were poor and often faced famine after wars, plagues, or crop failures.

International trade expanded and standards of living improved gradually through the 1700s in England, Scotland, and the Dutch Republic. Then the Industrial Revolution ramped up productivity and progress. The Glorious Revolution (1688) was part of the story as England followed the Dutch republic model instead of the French absolutist model. And Scotland had the good fortune to abolish its entire government in 1700 with union with England. (Recommending reading: How the Scots Invented the Modern World).

International trade expanded and standards of living improved gradually through the 1700s in England, Scotland, and the Dutch Republic. Then the Industrial Revolution ramped up productivity and progress. The Glorious Revolution (1688) was part of the story as England followed the Dutch republic model instead of the French absolutist model. And Scotland had the good fortune to abolish its entire government in 1700 with union with England. (Recommending reading: How the Scots Invented the Modern World).

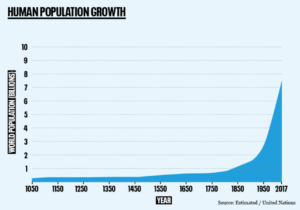

Coal power and expanding trade fed the Industrial Revolution of the Even in Europe abject poverty was normal, and famines not unusual before the Industrial Revolution. Poverty, best measured by child mortality and life expectancy, has receded in market economies since the 1800s. Living standards have continued to improve, with many more children surviving to become adults and have their own children. Before the 1800s, the world’s population grew very slowly.

Europe’s increasingly fast population growth led Thomas Malthus to write An Essay on the Principle of Population (1826, 6th Edition) claiming population naturally grows faster than food production. As farmers cultivate more land they soon face less-productive land higher costs rising and lower productivity. Malthus later changed his views to see innovation could deal with increasing population, but followers and later “neo-Malthusians” didn’t get that message

Europe’s increasingly fast population growth led Thomas Malthus to write An Essay on the Principle of Population (1826, 6th Edition) claiming population naturally grows faster than food production. As farmers cultivate more land they soon face less-productive land higher costs rising and lower productivity. Malthus later changed his views to see innovation could deal with increasing population, but followers and later “neo-Malthusians” didn’t get that message

Paul Ehrlich, author of The Population Bomb, continued to call for coercive population controls both to reduce poverty and reduce pressure on the environment. (Population pessimist Paul Ehrlich made a bet with technology optimist Julian Simon, about the future. See How Julian Simon Won a $1,000 Bet with “Population Bomb” Author Paul Ehrlich (FEE, March 8, 2018)

Poverty, industrial England, and “surplus” population were woven into Charles Dickens popular novels as well as Karl Marx’s economics writings. In Scrooge on Foreign Aid and Human Flourishing (Economic Thinking, 2019), I contrast the roles both speculation and charity for reducing poverty in industrial England.

Scrooge is portrayed as a businessman speculating in grain. He purchases grain and stores it, hoping to sell at higher prices in the future. Critics of speculators like Scrooge blame them for raising grain and therefore bread prices, hoping to profit and making life harder for the poor. However, there is more to the story. Speculators are time-traders, shifting today’s goods into the future. Why might that be a good thing?

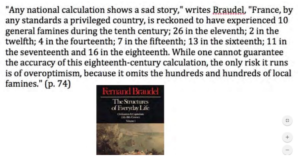

The great French historian Fernand Braudel lists famines in nearby France, in his stunning three-volume history: The Structures of Everyday Life: Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century:

The great French historian Fernand Braudel lists famines in nearby France, in his stunning three-volume history: The Structures of Everyday Life: Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century:

France by any standards a privileged country, is reckoned to have experienced [51 famines from 10th to 15th centuries], 13 in the sixteenth, 11 in the seventeenth and 16 in the eighteenth. While one cannot guarantee the accuracy of this eighteenth-century calculation, the only risk it runs is of overoptimism, because it omits the hundreds and hundreds of local famines…” (p. 74)

Economist and journalist Henry Hazlitt in The Conquest of Poverty (1972) offers an overview of tragic world famines:

1586: famine in England giving rise to the Poor Law system. 1661: famine in India; no rain fell for two years. 1769–70: great famine in Bengal; a third of the population—10 million persons—perished. 1783: the Chalisa famine in India. 1790–92: the Deju Bara, or skull famine, in India, so called because the dead were too numerous to be buried.

Hazlitt also notes the fast population increase in England and Wales after 1750:

The population of England and Wales in 1700 is estimated to have been about 5,500,000; by 1750 it had reached some 6,500,000. When the first census was taken in 1801 it was 9,000,000; by 1831 it had reached 14,000,000. In the second half of the eighteenth century population had thus increased by 40 percent, and in the first three decades of the nineteenth century by more than 50 percent. This was not the result of any marked change in the birth rate, but of an almost continuous fall in the death rate.

The fast expanding factories industrializing England and western Europe didn’t automatically make poor peasants prosperous. The increased trade and production lowered the costs for everyday goods enabling the now less-poor to not starve when war or bad weather caused crop failures. The Napoleonic Wars devastated much of Europe and the English government went deeply in debt to finance winning the war. Decades of higher taxes to pay back that debt reduced wages and kept England poorer. That’s the world both Karl Marx and Charles Dickens experienced and wrote about.

Socialists like Karl Marx came to believe that reorganizing the economic system could increase production still further, and make “distribution” more equal. Wages could be increased he thought by reducing the profits extracted by the capitalists.

The Power of The Communist Manifesto

Karl Marx wrote influential books about economics and social order, including The Communist Manifesto (1848, coauthored Friedrich Engels) and Das Kapital (Capital, 1867). Marx and Engels called for revolution. They advocated a scientific socialism with workers (the proletariat) would in control of the means of production (the capital, or factories). (Actually Marx and later Lenin called for “workers councils” to have control).

Marx and other socialists argued (and still argue) that owners (the bourgeoisie) take unfair advantage of their control of capital (factories) keeping wages down for the proletariat and draining away unearned company income as profits (returns to capital).

From Adam Smith and other classical economists, came the view of people of different economic classes. Producing goods required land, labor, and capital. So the land owning classes (the aristocracy) received rent from farms and factories, the laborers, whether farm or factory labor earned wages for their time, and the capitalists took profits for providing the tools, the farm or factory machinery.

Missing from this early view of capitalism was the entrepreneur, the businessman with productive ideas but not land or money to finance new enterprises. Farmers were sometimes entrepreneurs, devising new ways to fertilize and manage their land, increasing food production per acre. Factory owners and workers were sometimes entrepreneurs, devising new labor-saving technologies.

Stepping back from the socialism debate over who should control factories and how profits are distributed are bigger questions of: what should factories produce and how? Socialists (and Marxists) can debate over who should own and run Ford, GM, Toyota, and Tesla factories. But who decides what car designs to pursue, or whether engines should be powered by gasoline, diesel, electricity (or steam)?

This is part of the great Socialist Calculation Debate that the Austrian economists launched against the Marxists and socialists. (See: Ludwig von Mises and the Calculation Debate, FEE Video 2011). The Marxists said they would abolish prices and markets but Ludwig von Mises asked: how then will society’s scarce resources be allocated? Without prices, how can business or government compare alternate uses of scarce resources like labor or lumber, coal, iron, or copper. For more on the key role of prices in mobilizing knowledge and preferences, see F.A. Hayek’s classic journal article: “The Use of Knowledge in Society.”

Back to the Nineteenth Century…

Marx’s economic theories should be put in the context of the Industrial Revolution in Western Europe. England, German, and France were rapidly industrializing. Incredible progress, but many observers didn’t see it that way because populations were growing fast and though not dying of starvation, most still stayed poor. Population increased, agricultural productivity increased, international trade expanded, and vastly more energy was available from coal powering transportation, mining, and factories.

Industrial and farm workers weren’t having more children, instead far fewer were dying. Across Western Europe populations expanded through the 1800s. Millions went to work in new factories and millions left Europe for new worlds:

From 1815 to 1932, 60 million people left Europe (with many returning home), primarily to “areas of European settlement” in the Americas.

Economist Mark Skousen provides an overview of Marx and his ideas in this 1998 article. What’s Left of Marxism?: Intellectual Marxism Lives On (The Freeman). Marx’s continued influence comes not from his three-volume Das Kapital, but instead from the literary power of his short essay:

…there are also a handful of declarations, pamphlets, and small books that have changed the world. Thomas Jefferson’s “Declaration of Independence,” Tom Paine’s Common Sense, and the Four Gospels of the New Testament are good examples.

The Communist Manifesto fits into the second category. In rereading it, I couldn’t help feeling the passionate power, the pungent style, and the astonishing simplicity of Marx and Engels’s words. I can easily see how a young revolutionary could be swayed by these unforgettable lines: “A specter is haunting Europe—the specter of Communism. . . . The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. . . . Let the ruling classes tremble at a communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. WORKING MEN OF ALL COUNTRIES, UNITE!”

For more on the early enthusiasm about Soviet communism in America see Max Eastman’s Reflections on the Failure of Socialism:

When the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in October 1917, shocking the whole world of progressive and even moderate socialist opinion, I backed them to the limit in the Liberator. I raised the money to send John Reed to Russia, and published his articles that grew into the famous book, Ten Days That Shook the World. I was about the only “red” still out of jail in those violent days, and my magazine was for a time the sole source of unbewildered information about what was happening in Russia. Its circulation reached a peak of sixty thousand.

And see Rose Wilder Lane (daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder) essay “Give Me Liberty” (1936)

In 1919 I was a communist. My Bolshevik friends of those days are scattered now; some are bourgeois, some are dead, some are in China and Russia, and I did not know the last American chiefs of the Third International, who now officially embrace Democracy. They would repudiate me even as a renegade comrade, for I was never a member of The Party. But it was merely an accident that I was not. …

The picture of the economic revolution as the final step to freedom was false as soon as I asked myself that question. For, in actual fact, The State, The Government, cannot exist. They are abstract concepts, useful in their place, as the theory of minus numbers is useful in mathematics. In actual living experience, however, it is impossible to subtract anything from nothing; when a purse is empty, it is empty, it cannot contain minus ten dollars. On this same plane of actuality, no State, no Government, exists. What does in fact exist is a man, or a few men, in power over many men. …

I came out of the Soviet Union no longer a communist, because I believed in personal freedom. Like all Americans, I took for granted the individual liberty to which I had been born. It seemed as necessary and as inevitable as the air I breathed; it seemed the natural element in which human beings lived.

The thought that I might lose it had never remotely occurred to me. And I could not conceive that multitudes of human beings would ever willingly live without it.

It happened that I spent many years in the countries of Europe and Western Asia, so that at last I learned something, not only of the words that various peoples speak, but of the real meanings of those words. No word, of course, is ever exactly translatable into another language; the words we use are the most clumsy symbols for meanings, and to suppose that such words as “war,” “glory,” “justice,” “liberty,” “home,” mean the same in two languages, is an error.

Everywhere in Europe I encountered the living facts of medieval caste and of the static medieval social order. I saw them resisting, and vitally resisting, individual freedom and the industrial revolution.”