Notes on NCFCA Policy Topics [2017-2018]

[Post below on 2017-2018 topics, post on 2019-2010 NCFCA topics is here.]

NCFCA posted potential debate topics for 2017-2018:

A. Resolved: The United States Federal Government should significantly reform its budget and appropriations process.

B. Resolved: The United States should significantly reform its policies regarding higher education.

C. Resolved: The United States Federal Government should significantly reform one or both of the following: Medicare or Social Security.

All are interesting and important topics for research and debate.

And each involves federal policy disasters decades in the making.

For higher education, federal policy has featured easy credit for students which have both burdened college student with heavy debts and increased higher education costs. The website Student Loan Hero offers this overview:

You’ve probably heard the statistics: Americans owe over $1.4 trillion in student loan debt, spread out among about 44 million borrowers. That’s about $620 billion more than the total U.S. credit card debt. In fact, the average Class of 2016 graduate has $37,172 in student loan debt, up six percent from last year.

“Does Federal Student Aid Cause Tuition Increases? It Certainly Enables Them,” (Forbes, October 8, 2015) notes arguments for and against the claim that federal student loans and grants cause increases in college tuition, then notes:

First, a handful of recent, well-designed studies do find a robust relationship between changes in student aid and tuition prices. For instance, we’ve got new evidence from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York that sticker prices at colleges with lots of borrowers increased after federal student loan programs expanded. They find that for every additional dollar in subsidized loans, colleges raised sticker prices by about 65 cents (the effect of Pell Grants was smaller (55 cents) and less robust to the addition of control variables).

Economist Richard Vedder’s 2004 Going Broke by Degree: Why College Costs So Much explains that most increases on college operating costs have little if anything to do with actual college instruction. This AEI overview of the book notes:

The dramatic rise in university tuition costs is placing a greater financial burden on millions of college-bound Americans and their families. Yet only a fraction of the additional money colleges are collecting—twenty-one cents on the dollar—goes toward instruction. And, by many measures, colleges are doing a worse job of educating Americans. Why are we spending more—and getting less? In Going Broke by Degree, economist Richard Vedder examines the causes of the college tuition crisis. He warns that exorbitant tuition hikes are not sustainable, and explores ways to reverse this alarming trend.

This November 1, 2016 Forbes column, “Are We Still Going Broke By Degree?“, Richard Vedder reviews current trends. And his Center For College Affordability and Productivity has this post “Thirty-Six Steps: The Path to Reforming American Education,” (January 22, 2015). The affirmative case almost writes itself: “…to solve these problems we offer this thirty-six step reform policy…”

“…significantly reform one or both of the following: Medicare or Social Security.”

Medicare and Social Security are ripe for reform. For decades market-oriented think tanks with Cato Institute and Heritage Foundation have published studies showing Social Security and Medicare programs were unsustainable and would bankrupt the country. The good and bad news for students considering this resolution is that now, decades later, the end is much, much closer.

First though, on the “things are okay” side, is Medicare Is Not “Bankrupt”: Health Reform Has Improved Program’s Financing (July 18, 2016) from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which begins:

Claims by some policymakers that the Medicare program is nearing “bankruptcy” are highly misleading. Although Medicare faces financing challenges, the program is not on the verge of bankruptcy or ceasing to operate. Such charges represent misunderstanding (or misrepresentation) of Medicare’s finances.

Social Security, Medicare Face Insolvency Over 20 Years, Trustees Report (Wall Street Journal, June 22, 2016). Over decades Social Security and Medicare generated surpluses. With private insurance, payments made are invested by young workers, then drawn down in old age after workers retire. But Social Security and Medicare were set up as government transfer programs instead of insurance programs. So each month’s income was paid out to current beneficiaries and everything left over just spent by the federal government. Somewhere this is a file cabinet with a folder full of IOUs that in theory the federal government owes the Social Security and Medicare trust funds.

Social Security goes into deficit by the end of this decade, and begins to draw on its file cabinet trust funds. The WSJ story notes:

Social Security, designed as a pay-as-you-go program, has been paying out more in benefit dollars than it collects in taxes since 2010. Its annual balances have remained positive due to interest payments it earns on trust-fund assets. By 2020, however, it will pay out more than it collects, even after accounting for interest payments, according to the latest report. After that, it would have to sell assets from its trust fund to pay benefits.

And:

Social Security faces depletion by 2034, which would trigger a 21% across-the-board benefit cut if Congress doesn’t act. More than 49 million Americans collected retirement benefits through the program last year, and nearly 11 million received payments from a separate disability-insurance program.

Shifting Social Security and Medicare from state-run transfer programs into genuine insurance programs offers a reasonable path away from the coming problems. Consider that courts have secured homeschool families rights to opt-out of problems they see in government schools. The solution isn’t ideal, since homeschool family still have to pay taxes for public schools their children don’t attend (plus pay costs for home education).

A similar option would allow people to opt-out of Social Security and Medicare by providing for their own retirement savings and medical insurance. Obligating those opting-out for the Social Security and Medicare costs of those still in the system seems unfair, but no more unfair than forcing homeschool families (and other families) to pay for schools their children don’t attend.

Additionally, allowing people to legally opt-out would help Social Security in the long term as it hurts in the short term. That is, those opting out would be setting aside savings to provide for their own retirement and therefore they would no longer be a financial burden on the Social Security system down the road. Similarly, as people set aside savings to purchase long-term medical insurance, they would reduce long-term liabilities for Medicare.

For homeschool families, it should come as no surprise that government designed and run Social Security and Medicare programs have stumbled in major ways, providing far lower value that private alternatives would have. “Still a Better Deal: Private Investment vs. Social Security,” (Cato Policy Analysis, February 13, 2012) explains:

Opponents of allowing younger workers to privately invest a portion of their Social Security taxes through personal accounts have long pointed to the supposed riskiness of private investment. The volatility of private capital markets over the past several years, and especially recent declines in the stock market, have seemed to bolster their argument.

However, private capital investment remains remarkably safe over the long term. Despite recent declines in the stock market, a worker who had invested privately over the past 40 years would have still earned an average yearly return of 6.85 percent investing in the S&P 500, 3.46 percent from corporate bonds, and 2.44 percent from government bonds.

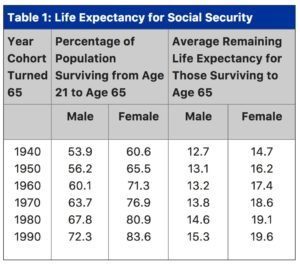

Also, adjusting the Social Security retirement age seems reasonable since people live far longer than they did when the retirement age was originally set. “Life Expectancy for Social Security” notes that life expectancy statistics can be misleading:

…Life expectancy at birth in 1930 was indeed only 58 for men and 62 for women, and the retirement age was 65. But life expectancy at birth in the early decades of the 20th century was low due mainly to high infant mortality, and someone who died as a child would never have worked and paid into Social Security. A more appropriate measure is probably life expectancy after attainment of adulthood.

As Table 1 shows, the majority of Americans who made it to adulthood could expect to live to 65, and those who did live to 65 could look forward to collecting benefits for many years into the future. So we can observe that for men, for example, almost 54% of the them could expect to live to age 65 if they survived to age 21, and men who attained age 65 could expect to collect Social Security benefits for almost 13 years (and the numbers are even higher for women).

Social Security’s problems are partly from increased lifespans, partly from expanding benefits beyond just retirement, but mostly from the baby boom now retiring and the “baby bust,” the smaller cohort now working and paying in. Increased immigration has helped increase the working age population, but most of these workers will be retiring after the current system is predicted to fail.

“How Can the U.S. Salvage Social Security?,” (The Atlantic, April 5, 2016) frames the problem as fairness in balancing reforms that raise Social Security revenue with other reforms that reduce costs. The article leads with suggestions that Social Security payroll taxes be increased and the earnings cap be raised, then discusses proposals to reduce benefits to wealthy families, and to raise the retirement age.

George Pearson, writing 20 years ago (Social Security: A Permanent Fix, Cato Commentary, May 1, 1997), makes the key point that Social Security was originally designed as a retirement supplement providing 1/3 of working income. But politicians boosted benefits to equal 2/3 of working income which led to insolvency so “the big fix” in 1983 raises payroll taxes to push problems into the future:

Social Security tax rates have increased 17 times since 1951. Counting both tax rate increases and adjustments of the wage base, payroll taxes have grown from 3 percent of $3000 in 1951 to 12.4 percent (not including Medicare) of $65,400 today.

The big fix was necessary because the original Social Security concept had changed. During the first 37 years of the program the maximum starting benefits paralleled the average hourly wage of the production worker at roughly one-third of that wage.

In 1972, Congress began increasing maximum Social Security benefits faster than increases in the hourly wage. As a result the maximum starting benefits today are nearly two-thirds of the average monthly wages. The old concept of providing a minimal retirement benefit has been replaced by the present, more generous approach of providing retirement income.

The Social Security program is under stress today not only because the ratio of workers to beneficiaries has changed (an issue that many talk about) but because the benefit payments have increased to provide a comfortable pension (an issue that few talk about).

Pearson then compares the U.S. Social Security problems to those face by Chile in 1983:

When the Social Security committee looked at different options for fixing the program in 1983, the Chilean model was not considered an option. In 1924, Chile became the first country to adopt a Social Security program. In 1981, when it ran into the same demographic problems that we are facing today, it privatized its program. So in 1983, there was not enough evidence to draw conclusions about the Chilean experiment.

Today there is considerable evidence that Chile made the right move. The country’s gross domestic product has been growing at the annual rate of 7 percent for the last 10 years. Its rate of savings is 28 percent compared to 3 percent in the U.S. Its pension fund has registered a 12.6 percent annual return since being established 15 years ago. Most telling is that 95 percent of all Chilean workers have chosen the private system that exists side-by-side with the state system.

The Social Security Administration website has an overview of the Chilean system: NOTE: Chile’s Next Generation Pension Reform (Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 68, No. 2, 2008), noting that other countries have passed similar reforms to their pay-as-you-go retirement systems:

In 1981, Chile introduced a new system of privately managed individual accounts, also called capitalization, replacing its public pay-as-you-go pension system (PAYG). Since 1990, 10 other countries in the region have adopted some form of what has become known as the “Chilean model”: Argentina (1994), Bolivia (1997),Colombia (1993), Costa Rica (1995), Dominican Republic (2003), El Salvador (1998), Mexico (1997), Panama (2008), Peru (1993), and Uruguay (1996).

This LA Times column is critical: “Chile’s privatized social security system, beloved by U.S. conservatives, is falling apart,” (August 12, 2016). And similar Financial Times article “Chile pension reform comes under world spotlight,” (September 12, 2016).

The Cato Institute responds to these attacks with “The Attack on Chile’s Private Pension System,” (August 16, 2016).

A 2010 WSJ/Cato op-ed on privatizing Social Security is “Private Social Security Accounts: Still a Good Idea.” And a related 2017 Heritage Foundation article “Government Makes The Poor Poorer,” links the Social Security program to rising inequality in the U.S.:

Social Security is the greatest swindle of the poor ever. A new study by Peter Ferrara for the Committee to Unleash Prosperity shows that the average poor person who works 40 hours a week during his or her working life would retire with a larger monthly benefit and would have $1 million or more in an estate that could be left to a spouse or children at death if they could simply put their payroll tax dollars into a personal 401k retirement account and tap into the power of compound interest.

Under Social Security poor (and middle class) households leave next to nothing for their kids at death. So Social Security robs nearly every low and middle income family with a full time worker of at least $1 million over their lifetime. What a deal!

The Social Security/Medicare topic gives students plenty to research and will lead them into U.S. history, politics, and economics.

For a more in-depth look at Social Security and Medicare as part of the expansion of welfare state programs in the U.S. and Europe, see the Atlas Network online book After the Welfare State (pdf).