Informal K-12 and Higher Education: U.S. and Developing World

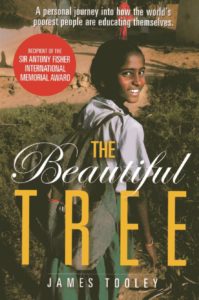

James Tooley, a professor of education policy at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, traveled the world researching The Beautiful Tree and describes the popularity of informal schools for low-income families in India and Africa.

In India, Nigeria, and Ghana, government officials explained to Tooley that private schools in their country were for the wealthy and schools for the poor would have to be free since poor families can’t afford tuition fees.

But in India Tooley stumbled upon a diverse network of informal schools:

While researching private schools in India for the World Bank, and worrying that he was doing little to help the poor, Professor Tooley wandered into the slums of Hyderabad’s Old City. Shocked to find it overflowing with small, parent-funded schools, he set out to discover if they could help achieve universal education. So began the adventure lyrically told in The Beautiful Tree—the story of Tooley’s travels from the largest shanty town in Africa to the mountains of Gansu, China, and of the children, parents, teachers and entrepreneurs who taught him that the poor are not waiting for educational handouts. They are building their own schools and learning to save themselves.

Tooley discovered hundreds of small private schools scattered across poor communities in Africa as well, even in a small fishing village in Ghana were five private schools compete with a foreign-aid funded state school. Parent-funded schools, operating informally (that is, without government approval), offered choice for parents and incentives for teachers.

This short video from Poverty Cure (a Christian nonprofit) explains:

This 2012 article in The Guardian asks: “Professor James Tooley: A champion of low-cost schools or a dangerous man?” Here is link to a 2012 TED video with more on this research: “How private schools are serving the poorest: Pauline Dixon at TEDxGlasgow.”

Similar expansion of informal schools for low-income families occurred in 18th and early 19th Century Scotland. Most in Scotland then were as poor as in the developing world today. In both cases population growth and demand for education by parents combined with a slow response by state and church schools opening doors for local teachers and education entrepreneurs. E. G. West, in Education and the Industrial Revolution reports the growth of Scottish “adventure schools” in the early 1800s which had four times as many students at state, church, and endowed schools.

West reports an 1818 survey of Scottish schools which found 54,161 students in 942 Scottish parochial schools but 106,627 students in 2,222 private unendowed or non-legislated “adventure” schools. The parochial school system did not expand enough to serve rapid population growth in Scottish mill towns and cities.

E. G. West researched the combined Glasgow, Greenock, and Paisley population which “rose from 42,000 in 1750, to 125,000 in 1801, and to 287,000 in 1831.” Private schools expanded for this growing population, and charity schools developed to provide schools for orphans and children of the impoverished. “In the county of Lanark, including Glasgow, there were in 1818 fifty-six parochial schools with 3,437 children, the private schools figures were about six time bigger: 307 schools with 18, 270 pupils.”

Parents paid fees at both parochial and private schools, but private schools proved more flexible, offering various “á la carte” schooling with fees varying by course. West quotes the approving remark of Robert Lowe “In Scotland they sell education like a grocer sells figs.”

Wikipedia, in an entry on Scottish education history, includes this reference to Scottish adventure schools:

There were also large number of unregulated private “adventure schools”. These were often informally created by parents in agreement with unlicensed schoolmasters, using available buildings and are chiefly evident in the historical record through complaints and attempts to suppress them by kirk sessions because they took pupils away from the official parish schools. However, such private schools were often necessary given the large populations and scale of some parishes. They were often tacitly accepted by the church and local authorities and may have been particularly important to girls and the children of the poor. [Reference: R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-521-89088-8, pp. 115–6.]

Orphans and the very poor had options including fast-growing Ragged Schools which from the 1830s to 1870s provided free “industrial” schools for hundreds of thousands of the very poorest Scottish and English children. In Ireland Hedge Schools offered informal education (“Hedge Schools and Classical Education in Ireland,” (Crises, May 3, 2016) when the British outlawed Catholic teachers:

Throughout those dark days the hunted schoolmaster, with price upon his head, was hidden from house to house. And, in the summer time he gathered his little class, hungering and thirsting for knowledge, behind a hedge in remote mountain glen—where, while in turn each tattered lad kept watch from the hilltop for the British soldiers, he fed to his eager pupils the forbidden fruit of the tree of knowledge.

So examples of informal (or underground) education come from history as well as around the world today. I would argue that similar informal education is flourishing across the United States today as well.

“‘Unschooling’ takes students out of the classroom,” (USA Today, July 26, 2016) reports:

The U.S. Department of Education estimates that there are nearly 2 million homeschooled children, of which 10 percent are estimated to be unschooled. …

“Unschooling is allowing your children as much freedom to explore the world as you can bear as a parent,” says Patrick Farenga, author and president of Holt GWS, an organization dedicated to continuing the mission and teachings of the late John Holt, considered to be a founder of the unschooling movement.

A John Holt website with more information is here. (John Holt quote link the Facebook.com/theunschoolbus.)

A John Holt website with more information is here. (John Holt quote link the Facebook.com/theunschoolbus.)

A similar (I think!) unschooling approach is found in Montessori Schools, following the teaching of Maria Montessori. From the American Montessori Society webpage:

More than 4,000 Montessori schools dot the American landscape, offering a unique educational model to families nationwide. Thousands more bring the Montessori method to every corner of the world.

Montessori schools can be found in rural, urban, and suburban settings; in working-class towns, affluent communities, and even remote villages. Some schools offer all levels of learning, from infant/toddler through the secondary (high school) level. Others offer only certain levels.

In the United States, most Montessori schools are privately owned. A growing number, however, are part of public school systems, making it possible for families of any means to give their child a Montessori education.

On Montessori schools, see also: “5 Discoveries In Neuroscience That Support Montessori Teaching,” (Exploring Your Mind, (March 22, 2017)

More formal informal schooling can be found in home-centered education, expanding over the last few decades and now involving an estimated two million students.

Here is U.S. Dept. of Education page for “Statistics About Nonpublic Education in the United States.” And the National Center for Education Statistics in “Measuring the Homeschool Population,” (January 4, 2017), reports 2016 homeschool survey data will be released in 2017. Christian evangelical families make up a large percentage of homeschoolers, and an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 are in Catholic homeschooling.

A 2012 Washington Post article: “Home-schooling pioneer Susan Wise Bauer is well-versed in controversy,” looks at controversies as homeschool has expanded. Susan Wise Bauer is author of The Well-Trained Mind: A Guide to Classical Education at Home and was long a speaker at homeschool conferences:

The English professor, historian, author of 18 books and holder of a doctorate in American studies from the nearby College of William & Mary is one of the forces behind America’s burgeoning home-schooling movement, which is growing about 7 percent each year. The National Home Education Research Institute estimates that there were 2.04 million home-schooled children in the United States as of 2010, about 4 percent of the nation’s school-age population. That’s almost double the 1.2 million home-schooled children in 2000. A June article in U.S. News & World Report said that home-schooled children graduate from college at higher rates than their peers, earn higher GPAs and are better socialized than most high school students.

California now has a strange mixture of “home-charter” schools, following state programs that allow homeschool families to declare themselves charter schools and receive state funding. “California Virtual Academies: Is online charter school network cashing in on failure?,” (The Mercury News, April 16, 2016, UPDATED: January 11, 2017), looks at the debate:

The TV ads pitch a new kind of school where the power of the Internet allows gifted and struggling students alike to “work at the level that’s just right for them” and thrive with one-on-one attention from teachers connecting through cyberspace. Thousands of California families, supported with hundreds of millions in state education dollars, have bought in. …

K12 is the nation’s largest player in the online school market. In California, it manages four times as many schools as its closest competitor, filling a small but unique niche among the state’s roughly 1,200 charter schools. And despite a dismal record of academic achievement in California and several other states — including Ohio, Pennsylvania and Tennessee — the business regularly reports healthy profits.

“EDUCATION: Why Inland charter schools are booming,” (Press-Enterprise, May 30, 2016) reports on other California parent-managed charter schools. Also “Will LA’s recent school board election kick-off a national wave of pro-charter school expansion?,” (trustED, June 1, 2017)

Innovation and free online video and conference tools expand options for informal schooling in the U.S. and around the world. “The classroom beyond,” (The Hindu, June 8, 2017), begins:

The idea of education has undergone a vast change. A classroom is no longer thought of as a confined space with a lecturer and students. Today, with a high-speed internet connection and a willingness to learn, one can acquire degrees from top-notch universities around the world.

In recent times, education has slowly been making a move online. Universities such as Harvard, MIT, Stanford and many more the world over are offering specialised courses, giving their global community of students an online learning experience.

The article discusses Tribr:

With an aggregation of 3,000 courses, 50 learning platforms and over 50,000 hours of online learning content, the platform urges students to explore their possibilities.

Unbound is a U.S. based service assisting high school and homeschool students earn transferable college credit while in high school.

Nearby community college also offer courses for high school students, and some for-credit college courses are taught in high schools. “AP, DC, DE, IB: An A–Z Guide to College Credit in High School,” (Noodle, June 8, 2015) explains:

There are lots of different programs for students eager to get started with college work — Advanced Placement (AP), dual credit (DC), dual enrollment (DE), and International Baccalaureate (IB).

Online education services like Khan Academy offer hundreds of courses to support students in traditional, home, or unschooling environments. “Start homeschooling with Khan Academy,” is one of many webpages with online education resources.

Given these diverse and rapidly expanding schooling technologies and opportunities, what role could or should federal education funding and regulation play?

And shouldn’t policy debaters be able to earn college credit for their many hours researching and debating through the year?