Infinity Resource War: Thanos, 12 Monkeys, and Tomorrow’s Eco-Terrorists

With Marvel’s Infinity War showing on Netflix, millions who rarely venture to movie theaters can immerse themselves again in the Marvel universe. For Marvel readers, Thanos seems similar to Galactus facing the Fantastic Four in The Galactus Trilogy.

“If This Be Doomsday!” read the Fantastic Four cover, and the question wasn’t so different from questions posed at school about overpopulation and pollution. Not only in the make-believe world of comic books but in the classrooms of the 1970s and since, most every day was doomsday.

Hollywood showed endless doomsday nuclear disaster movies, from Godzilla to giant crabs (Attack of the Crab Monsters), to some fifty others listed on Wikipedia. Later nuclear power disaster movies like China Syndrome were popular, followed by various nuclear winter movies.

Doomsday scientists turned up in magazines and newspapers regularly, claiming the Earth would soon suffer from manmade global cooling, then temperatures rose so temperature models were revised and predicted global warming. Now models predict climate changing. (I don’t mean to make fun of global warming here. More on climate science research below.)

Before global warming and climate change emerged as reasons to mandate higher car mileage and subsidize wind and solar power, running out of oil and other resources was the rationale.

Americans were also told landfill space was running out, and we would soon have nowhere to send all our garbage. So the focus turned to recycling which would also allow dwindling natural resources to last longer.

Americans were told we’d run out of oil and gas unless we turned down the heat and wore sweaters at home, as explained by the President of the United States in a nationwide address (President Jimmy Carter – Report to the Nation on Energy). Long lines at gas stations were thought signs that the last days of oil were near (but price controls on oil production and gasoline sales, along with OPEC oil embargo, caused the shortages).

Earth Day in the 1970s was a new nationwide adventure for schools to awaken students to coming environmental crises. If we did not mend our ways and reduce pollution, reuse and recycle resources, and shift to green energy, oil would soon be gone, along with natural gas and key minerals like copper, zinc, platinum, and aluminum.

Environmental burdens from modern industrial production would fall on future generations, students were told in school lessons, Captain Planet cartoons (pro-CP link and anti-CP link), and United Nations reports on “unsustainability.” Classroom and UN lessons are similar today. See, for example, A Value Clash? Freedom versus Intergenerational Equity on United Nations claims of “ecological footprints” and “total biocapacity.”

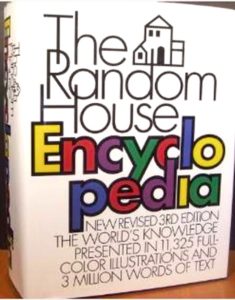

Are wealthy societies and economies burning up the Earth’s finite resources, condemning future generations to dystopian nightmare worlds? This was a popular claim and fear in the 1990s and presented even in the Random House Encyclopedia (1990 edition).

Will mankind crash into a natural resource wall in the not too distant future? An entry in the Random House Encyclopedia on “Earth’s dwindling resources” pictures a dump truck and charts the dates reserves of key resources used to construct it “may be exhausted” (Third Edition, 1990, p. 290). Platinum and lead may be gone in 2000, mercury and zinc in 2010, silver and tin in 2015, copper in 2030. Reserves for thirteen metals are shown running out before 2050, with the implication that this dump truck and the rest of modern society may collide with natural resource limits in our lifetime.

But resources didn’t run out and are now more plentiful than in the 1990s. Technologies for mining and oil and natural gas extraction keep improving. New innovations boost production, reduce pollution, and have expanded proven reserves in the ground. For an overview of finite yet expanding resources, see Natural Resources in the Library of Economics and Liberty.

Many articles and studies, though, continue to say Earth is on the brink and natural resources are about to run out. See, for example, Earth’s resources consumed in ever greater destructive volumes (The Guardian, July 22, 2018) which begins: “Humanity is devouring our planet’s resources in increasingly destructive volumes…”, and The Earth is exhausted – we’re using up its resources faster than it can provide (DW, January 8, 2017): “We’ve already used up more resources this year than our planet can regenerate….”

We can’t know for sure what tomorrow will bring (maybe an asteroid?), but we can know what prosperity and technological progress have brought in recent decades. Pollution levels have declined across the U.S. and the developed world (recently even in China), and both energy and resource use in wealthy countries is declining. But environmental progress isn’t good for action movie storylines or evening news headlines.

Here is a report from nearly 20 years ago: Environmental Progress: What Every Executive Should Know (PERC, 1999). The Environmental Defense Fund outlines recent environmental progress, Welcome to the Fourth Wave: A new era of environmental progress (EDF, March 21, 2018), as does Heritage, To Improve the Environment, Look to the Free Market (Heritage, March 6, 2018). Reason looks at the sustainability of expanding economies, Is Economic Growth Environmentally Sustainable? (December 16, 2016). And for the most of Earth that is ocean, advances with governance is improving fisheries management. See EDF’s Fisheries Solutions Center for details (and many past Economic Thinking posts on ocean policy). For more on environmental progress and challenges, see many PERC publications and stories here.

Economist Julian Simon argued in his books The Ultimate Resource and Ultimate Resource 2 (Princeton University Press), that Paul Ehrlich along with other environmentalists and population control advocates, were wrong about population, technology, and progress. Marian Tupy provides an update on Julian Simon’s research in Julian Simon Was Right: A Half-Century of Population Growth, Increasing Prosperity, and Falling Commodity Prices (Cato Institute, February 16, 2018). Pollution levels have fallen, and natural resources are more plentiful, all as world population increased and poverty rates fell dramatically:

… Between 1960 and 2016, the world’s population increased by 145 percent. 1 Over the same time period, real average annual per capita income in the world rose by 183 percent. 2

Instead of a rise in poverty rates, the world saw the greatest poverty reduction in human history. In 1981, the World Bank estimated, 42.2 percent of humanity lived on less than $1.90 per person per day (adjusted for purchasing power). In 2013, that figure stood at 10.7 percent .3 That’s a reduction of 75 percent. According to the Bank’s more recent estimates, absolute poverty fell to less than 10 percent in 2015. 4

Still all this progress didn’t slow the steady release of dystopian novels and movies. Predicted eco-catastrophes were no surprise for Marvel comics readers. In Marvel comics the world almost came to an end each month, until saved in the last pages by superheroes. Crime waves expanded issue by issue from neighborhoods, to cities, then nations and whole planets, as each cover revealed a new super villain wielding new powers.

In the late sixties and seventies inflation was a problem across the U.S. economy, distorting prices and investment decisions. Inflation also lifted the price of comics, from 10 cents to 12 to 15 to 25, the 50 cents and higher. Superhero power inflation was a separate challenge for Marvel writers. Superheroes would start fighting local gangsters, then super-gangsters, then powerful evil scientists, then eventually almost all-powerful aliens.

Jack Kirby explains his search for bigger story lines to help Marvel compete in the superhero comic marketplace:

My inspirations were the fact that I had to make sales and come up with characters that were no longer stereotypes. In other words, I couldn’t depend on gangsters. I had to get something new. For some reason, I went to the Bible, and I came up with Galactus. And there I was in front of this tremendous figure, who I knew very well because I’ve always felt him. I certainly couldn’t treat him in the same way I could any ordinary mortal. And I remember in my first story, I had to back away from him to resolve that story. The Silver Surfer is, of course, the fallen angel.

Thanos in Infinity War was concerned about overpopulation, and took action. That was Paul Ehrlich’s concern in The Population Bomb (1971), which sold over two million copies. Earlier Economic Thinking posts have looked at how overpopulation fears influenced education, foreign aid, and led to China’s leaders taking action with their one-child mandate.

So Thanos is a sort of intergalactic eco-terrorist, as was Galactus and other super-villains brought to life in comic books and movies. The movie 12 Monkeys lacked superbeings but had goofy and serious eco-terrorists first advancing “animal rights” and then an end to most of Earth’s population (past post on 12 Monkeys here). Today’s and tomorrow’s eco-terrorists can turn to gene splicing to engineer new microbes and diseases, or maybe they already have.

12 Monkeys Is the Apocalypse Movie We Need Right Now, (Vulture, November 21, 2018) provides an example of how negative environmental claims can combine with apocalyptic stories to lead people astray:

I’ve been thinking about 12 Monkeys a lot lately. It seems, these days, as though the human race has passed a Rubicon and is now on a straight path toward the end of days, or at least the end of the social order as we know it. The most obvious threat is not a virus, but rather our degradation of the biosphere. The U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has made it clear that our ongoing ecological hubris means there’s precious little chance we will avoid planetary upheaval of the worst variety, and suggests we will probably fall off a cliff in the next dozen or so years. We are still obligated to try to mitigate the extremity of the climate disaster, but the existence of that disaster is more or less a done deal.

(More below on the divergence between climate science research and IPPC review summaries for media and public relations.)

The Next Wave of Extremists Will Be Green (Foreign Policy, September 1, 2017) violence may come from edge environmentalist if they believe both that radical steps must be taken and yet no governments are taking these steps. (No dictator today to mandate to a billion Chinese that no family have more than one child.)

The necessary conditions for the radicalization of climate activism are all in place. Some groups are already showing signs of making the transition. And when they do, we may be ill-equipped for handling these new green hard-liners.

Radicals of all types share certain characteristics. According to Peter Neumann, the director of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) and author of Der Terror ist unter uns (“The Terror Is Among Us”), people who become radicalized typically have a “sense of grievance” — sometimes real, sometimes perceived — and a belief that legitimate channels for redress are shut off, inaccessible, or ineffective. There is also usually a social element, in the form of a charismatic preacher or ideology, that spurs people to seek emotional fulfillment through otherwise forbidden methods for redemption.

The Foreign Policy article author, Jamie Bartlett, believes that extreme climate catastrophes are coming, and may set off new terrorist acts by environmental extremists.

And when time runs out, as I’m afraid it will, books like Deep Green Resistance — a sort of how-to guide for radical environmentalists — urge abandoning ineffective peaceful routes and hint darkly that industrial sabotage is the only avenue left open. …

I recently visited a group of specialists who work on Islamist and far-right deradicalization and asked them how they would go about preventing green radicalization. Perhaps asking Greenpeace managers to deradicalize militant monkey-wrenchers? Or infiltrating Friends of the Earth to find recruiters? Maybe building a new model to spot signs of growing radicalization — university courses in the humanities, involvement in left-wing student groups, coupled with a growing interest in recycling — that could help the police spot early warning signs? No one was quite sure, but none of these prescriptions felt right.

Research, knowledge, discussion, and reasoned debate can help educate and deradicalize environmental extremists. And learning some history helps. Many past pseudo-scientific theories were turned into costly public policies around the world, including eugenics, overpopulation, and resource depletion in the U.S.

Today’s popular narratives of coming climate catastrophes follow decades of similar catastrophe claims predicted from overpopulation and running out of natural resources. The catastrophe narrative, (Climate, Etc., November 14, 2018) discusses why environmental catastrophes are so enduring and popular for so many, even as they morph to embrace new claims and fears:

Within the public domain, there is a widespread narrative of certainty (absent deep emissions cuts) of near-term (decades) climate catastrophe. This narrative is not supported by mainstream science (no skeptical views required), and in the same manner as an endless sequence of historic cultural narratives, propagates via emotive engagement, not veracity.

The catastrophe narrative is propagated by all levels of authority from the highest downwards, granting it huge influence, and differentially via favored functional arms of society, plus at the grass roots level. Over decades, various forms [of] the catastrophe narrative … typically feature powerful emotive cocktails (mixed emotions invoked simultaneously) and great urgency, which are highly adapted to undermining objectivity. …

Jacobs et al (in 2016 book) finds no merit in the claim ‘that catastrophic anthropogenic global warming is the mainstream scientific position’, i.e. mainstream science as represented by the IPCC AR5 working group chapters13, does not support the concept of a high certainty (absent action) of imminent global catastrophe. … A minority of scientists, some very vocal, believe that catastrophic scenarios are more realistic.

Yet New York Times readers and NPR listeners are told the opposite: that most climate scientists believe CO2 emissions will bring climate disasters and only a handful of hardened “climate deniers” oppose the dangers of climate change.

Hopefully speech and debate students can research these claims on their own, and share with the wider world the contrasting narratives of resilient economic progress vs. a fragile world of cascading environmental catastrophes.

Environmental end times, taught in books, movies, and classrooms (and touched on in Infinity War), can capture impressionable minds and hatch disasters far more deadly -than the ecosystem challenges of the coming decades.

See also:

• The Boy Who Cried Wolf Grew up to Be an Environmental Alarmist, (PERC, July 24, 2017)

• How Julian Simon Won a $1,000 Bet with “Population Bomb” Author Paul Ehrlich (FEE, March 8, 2018)

• Yes, Thanos Was Evil: Why Advocates Of Population Control Are Always Wrong, From Malthus To Marvel (RealClearPolitics, August 15, 2018)

1 Response

[…] and debate students, trying to place the ideas into the context they know. [See, for example, “Infinity Resource War: Thanos, 12 Monkeys, and Tomorrow’s Eco-Terrorists” (April […]