Family, Work, Community: Did Ebenezer Scrooge Dream a Better Life for Himself?

Charles Dicken’s novel, A Christmas Carol, was set in England in the early 1840s. We hope England and Europe escapes the cold of the winter of 1840-41. Modern industrial societies should be safe from winter freezes. That safety depends upon reliable modern energy. Coal, oil, natural gas can keep the English and other Europeans alive and even warm through winter.

Wind and solar energy may power the future, as advocates predict. But warmth this winter in the UK, Ukraine, and across Europe depends on fossil and nuclear energy. When the deepest winter cold descends across Europe, neither the winter sun shines nor winds blow enough. This winter natural gas from Russia has been cut off from Germany and reduced from Russia through Ukraine. Now European natural gas is imported from the US.

But let’s go back to Bob Cratchit, in the 1984 television version of A Christmas Carol, telling his employer: “the fire’s gone cold Mr Scrooge!” George C. Scott as Scrooge cooly replies: “… garments were invented by the human race as a protection against the cold. Once purchased they may be used indefinitely for the purpose for which they were intended… cold is momentary and cold is costly, there will be no more coal burnt in this office today, is that quite clear, Mr. Cratchit?” Similarly in 1977 US President Jimmy Carter, wearing a sweater, and sitting by a wood-burning (or natural gas) fireplace, advised the country to face the ongoing energy crisis with warm garments, and to turn their thermostats down. Carter was not reelected.

Nineteenth century energy plays a small part in Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol. My goal here is to engage students researching national debate topic on economic inequality, energy, and transportation policy. I’ll argue that current energy/transportation policies, if not reformed, can send England and the rest of Europe back to the days of Ebenezer Scrooge and Bob Cratchit quarreling over adding more coal to the office furnace.

I’ll make the case that England importing corn (Scrooge’s business on grain exchange), or importing and exporting coal, or importing or producing oil and natural gas today, can all be Christmas stories and economics lessons.

Scrooge departs his office on Christmas Eve to face a cheerful though crippled Tiny Tim, and from there heads to the grain exchange to tell buyers: “The price has gone up!” Scrooge is a merchant, a speculator. He’s purchased corn (wheat) and pays to warehouse it. If prices goes up enough over time he earns a profit. If the prices stay the same or drop, he has a loss. He is a time trader, shifting food into the future where he hopes it will sell for higher prices. Is he greedy? Or just hoping for people more hungry in the future than those in the present? By buying and storing grain now, he is pushing current prices up and thereby encourages both conservation and increased production. (Other merchants similarly speculate in coal, paying to warehouse it now in hopes of higher future prices. Higher prices for coal leads Scrooge to insist Cratchit burn as little as possible.)

Shifting from impoverished England of the 1840s to impoverished Africa, India, and Latin America today, how can people find and follow the shortest path from energy poverty to prosperity? Hans Rosling in his widely viewed TED talk, The Magic Washing Machine, explains the energy threshold today that few women live above: “the wash line.” Most women around the world wash clothes by hand, lacking access to energy for machines to reduce their burdens.

How can poverty be reduced in the developing world? Dickens, who attended an early 1800s English debating society, saw poverty all around him, and even worse in India and Africa. World poverty has been much reduced in the less than two centuries since Charles Dickens created Ebenezer Scrooge. Advances in energy availability, reliability, and density are at the center of this progress.

9. Global extreme poverty: Present and past since 1820 (OECDiLibrary)It took 136 years from 1820 for our global poverty rate to fall under 50%, then another 45 years to cut this rate in half again by 2001. In the early 21st century, global poverty reduction accelerated, and in 13 years our global measure of extreme poverty was halved again by 2014.

Which Scrooge best reduces poverty and suffering in the world? The old and greedy Scrooge hoarding grain and gold, or Dickens’ Scrooge transformed to philanthropist tossing coins to he poor around him? More of the story in: How the Movies Invented Christmas (Wall Street Journal, December 20, 2018):

It is a well-attested historical fact that the publication of “A Christmas Carol,” the best-loved book by the best-selling English-language novelist of the 19th century, had the unintended consequence of reintroducing Christmas to countless Britons and Americans who had stopped observing the holiday. And its influence continues to be felt: Dickens’s 1843 novella has been adapted more than three dozen times for film and television since 1901… Moreover, the vast majority of America’s most popular Christmas films contain plot twists that are derived, at one or more removes, from “A Christmas Carol.”

Dreams opening a window to the past reveal Scrooge as a young man not yet hardened by decades of narrowly pursuing trade and wealth. But we see Scrooge in his later years asked to help the poor by selling, perhaps giving, some of his stored grain.

Instead of giving turkeys to poor families like Bob Cratchit’s, Scrooge could have given turkeys to local (or distant) aid agencies. But would grain or turkey donations be a reasonable or effective way to help the poor in 1840s England or across Europe, India, or Africa in the 2020s?

George C. Scott brought Charles Dickens’ Ebenezer Scrooge to life in a 1984 television special. Scott played Scrooge as a competent and thoughtful businessman who finds both Christmas and philanthropy a waste of time and money. Scrooge’s eyes are opened through a series of ghostly nightmares showing him his past and likely future.

Dickens’ novel and the various movie and cartoon versions are seen today as indictments of greed and business (plus income inequality), as well as celebrations of the joys of family, Christmas, and giving to those less fortunate.

Looking at this classic story through an economic freedom lens illuminates lessons about work, choices, and charity very different from the usual take on Scrooge. We can envision a last chapter to the story with Scrooge living his happier life without breaking long-held business principles.

People—especially successful business people—can get wrapped up in their work and lose touch with the rest of their lives. Engagement in civil society brings many unexpected and hard-to-quantify pleasures.

Research in the value of going to more parties is discussed in this Marginal Revolution post, citing “Go to More Parties? Social Occasions as Home to Unexpected Turning Points in Life Trajectories.” Parties revive and engage:

They do this by pulling people into a special realm apart from normal life, generating collective effervescence and emotional energy, bringing usually disparate people together… Rather than a time out from “real” life, social occasions hold an outsized potential to unexpectedly shift the course that real life takes. Implications for microsociology, social inequality, and the life course are considered.

Apart from time out for parties and other social gatherings, philanthropy can be satisfying to the giver as well as helpful to the receiver. But effective charity turns out to be more challenging than enjoyable social gatherings.

The story begins with Scrooge successful in business but having let his personal and social world fade. He long ago let his love relationship drift away and now had deep regrets. After a difficult childhood, he gradually gained a kind of comfort in solitude and emotional isolation. As is usual in novels and movies, nothing positive is said or implied about his work. No glimmer of understanding that he must be providing a valued service in order to stay in business and accumulate savings. Focused businessmen like Scrooge can lose track of their family and social lives and years later find themselves wealthy but alone.

Secondly, the story features an interesting, if subtle, attack on government welfare (and by implication, foreign aid). Scrooge is asked to donate to a relief fund. He answers that he pays taxes for just such purposes. Why don’t the homeless go to existing poor houses or to prisons? Scrooge asks. The NGO [Non-Governent Organization] private-relief fund-raisers ask him if he has ever seen the government relief houses?

Scrooge answers no, he hasn’t–tax-supported relief houses give the emotionally-distant Scrooge an excuse to not take personal responsibility for the poor. He has already paid, he claims, through his taxes. He uses government-funded welfare as an excuse to avoid supporting private relief. With no state-run poor houses in England, Scrooge might still have said: “Bah, Humbug!” and “free-ride” on donations of others. That is, he might free-ride (an economics term) by relying on others to give enough to the homeless and to charities. Scrooge would benefit from fewer homeless on the streets without spending a dime on donations (he is greedy in the story, after all).

Perhaps we can identify with Scrooge’s desire to avoid facing the plight of the homeless in his community. Scrooge could perhaps have been convinced to support private relief just to keep the homeless out of his way. Still a selfish motive, but one requiring helping others in order to help himself. Scrooge could have invested in enterprises hiring the unfortunate or unwise and helping them get back on their feet. Consider too that Scrooge’s grain speculation could very well be helping the poor as effectively as charity (more on this possibility below).

Had Scrooge invested in a job-training firm, for example, he could carry business cards promoting his job-training services to put in the cups of the homeless. In this way he could have helped the poor and profited as an investor in training-services at the same time (perhaps naming his enterprise Scrooge University).

Many for-profit as well as nonprofit organizations provide job-training services and generate income through job-placements. The poor learn skills and pay a portion of their later salaries back to the job-training/job-placement firm.

My great-great-grandfather, Dr. Thomas Guthrie, helped start the Ragged Schools for Children in Scotland. He went to the Scrooges of his day (the 1840s) and convinced them to contribute. The Ragged Schools started in Scotland and grew gradually. Andy Murray, in his Ragged Theology blog explains the first Ragged School and its inspiration:

The first or ‘original’ ragged school in Edinburgh was established in 1847 in a small room on the Castle Hill. The main building that was eventually used is now part of Camera Obscura and the open bible can still be seen above the door with the words ‘Search the Scriptures’ (John 5 v 39) engraved on it. Guthrie says that the inspiration for the ragged school movement was from John Pounds of Portsmouth (1766-1839). Pounds was a dockyard worker who at the age of 15 fell in to a dry dock and was crippled for life. As he recovered he taught himself to read and write and became a cobbler. Pounds started to teach local children to read and write free of charge. He also taught them carpentry, how to cook and how to repair shoes while offering them food and shelter at the same time. (Source.)

There were 192 Ragged Schools in operation at its peak with 20,000 destitute children attending each year. An estimated 300,000 attended overall, from the 1840s to 1880s. The English government later saw the Ragged Schools as unwanted competition for their poor houses and new government schools, and worked to replace the Ragged Schools. Students apparently preferred the industry-training received as part of their education at the Ragged Schools. The UK government went so far as to sue to force students out of Ragged Schools and into government schools. Glimpse this fascinating story here (see section: “Tensions with the state system”).

Because Scrooge believes he has discharged his obligation to help the poor (thanks to state-mandated poor-houses), he loses touch with that part of the world. He doesn’t bother looking into the management and operation of poor houses because their tax-funding insulates them from private reform. And he knows he wouldn’t be allowed to withhold his taxes if he found them badly managed.

Had he been surveying private alternatives to support, he would likely investigate how his money would be used. The story doesn’t show him doesn’t much to investigate after being transformed. He just gives a big donation to the private relief effort he refused the day before. But even so, he will surely take an interest in that private relief project after donating a huge sum to it. He would be angered as well as embarrassed if the relief effort he supported turned out to be poorly managed.

Scrooge in a world of tax-funded poor houses is less likely to be drawn into civil society philanthropies (and their fundraising gatherings) that might have opened up his life (reducing his need of spiritual shock-therapy).

His very skeptical eye would be a valuable service for private charities, as he seems to understand that good intentions matter less than good results. He would probably be a better trustee of a private charity than his “do-gooder” nephew, for example.

George C. Scott’s Scrooge notes with disapproval his nephew’s offer to overpay Cratchit’s son. Scrooge understands that overpaying for a young person’s first job can have negative consequences. It breaks the connection between a person’s productivity and their pay. It confuses charity with wages in the mind of both the employee and employer.

The intricate dance toward “just” or market wages not only pits each worker against others willing to work for less, it pits each employer against other employers willing to pay more. When employers get greedy and try to hold wages below the marginal earnings each worker brings the firm, other employers have a profit opportunity if they can hire that worker away.

A smaller slice of earnings from a hundred or a thousand workers can add up to far more than a larger slice from a dozen. Henry Ford earned far less profit per worker and per car sold than did Henry Royce. But in the end, he did alright. See, for example, the 2006 book: Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits.

The push for labor services leads employers into a bidding war that narrows the gap between what workers earn for firms and what they are paid. Competition for workers is frustrating for employers who hire and train new employees only to see them lured away by competitors.

The explanation for Bob Cratchit’s low pay is likely his limited skills, responsibility, and productivity at the firm of Scrooge and Marley. In fairness to Mr. Cratchit, it may not be his fault that Scrooge has been holding on too tight and not delegating enough. Marley may have offered Scrooge more opportunities to learn and share responsibilities at the firm than Scrooge had so far given to Cratchit. Either could be blamed, but if Scrooge can’t find a way to delegate more responsibility to Cratchit, increasing his value to the firm and his wages, Cratchit should search for another firm that can better manage and develop (and pay for) his skills.

Seeing the Ghost of Famine future

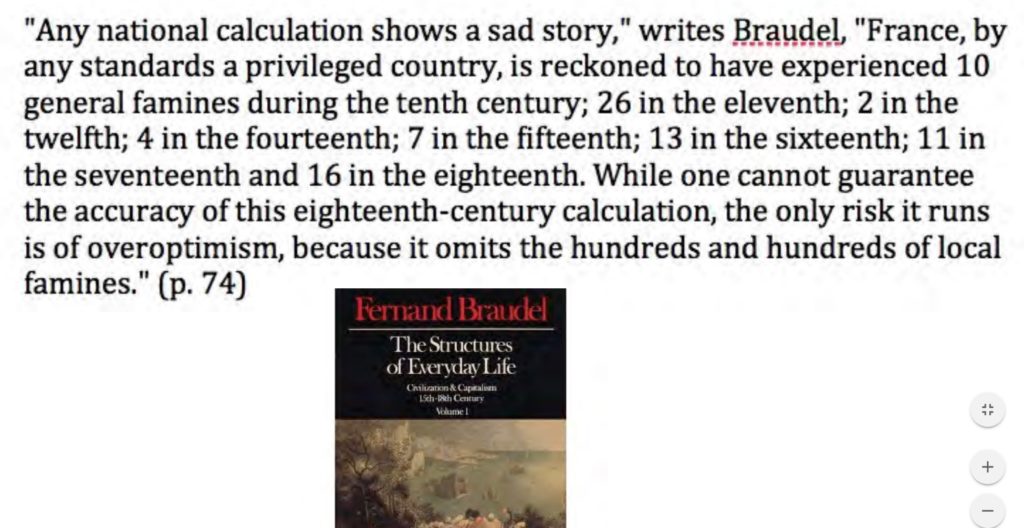

The ghosts of terrible futures that never happen, but might have… Imagine Ebenezer Scrooge dreaming a terrible famine would soon strike. Perhaps nightmare tariffs on imported grain coupled with bad harvests in England drive corn prices beyond the reach of the poor and spread famine across the land. Famines in Scrooge’s time were not rare and he would have lived through one in his youth. The Europe-wide famine of 1816/17 followed poor harvests across Europe and the general destruction of the Napoleonic Wars. Crop yields in Western Europe fell 75 percent triggering widespread famine and death.

Consider French historian Fernand Braudel’s count of national famines in nearby France, in The Structures of Everyday Life: Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century Volume 1, “…13 in the sixteenth [century], 11 in the seventeenth and 16 in the eighteenth…”

For a businessman like Scrooge, a vision of bad weather might lead to careful review of news across Europe as harvests approached. News of conflicts or bad harvests could be reason enough for taking a major investment position. Early on in the movie George C. Scott’s Scrooge visits the city grain exchange to do some business. He holds out for a higher price for corn in his warehouse, and is accused of hurting the poor through his greed. But is holding out for higher prices really hurting the poor? Yes and no.

His “hoarding” or speculating on grain does raise the price today. But it also has the consequence of pushing prices down in the future. Scrooge has a vision of scarcer grain and higher prices in the future (otherwise he would sell at today’s prices). He is raising the price of grain for the poor (and everyone else) today, in exchange for lowering the price in the future. If his vision proves true, he will have performed a service for society by pushing all to conserve now a resource that will be more scarce in the future.

Speculators like Scrooge are time-shifters. Whether or not inspired by ghostly visions, they trade goods through time. Scrooge fills his warehouse with grain then turns the dial on a time-machine to shift his grain to the future. It is an expensive and risky enterprise. Who knows what the future will bring? Speculators make informed guesses about the future. If their hunches are right, their fourth-dimension transportation system earns profits, even after paying rent on warehouse space and interest on money tied-up over time. If they guess wrong they lose. And after too many wrong guesses, both Scrooge and Cratchit would be looking for new work.

Across Europe in old city-centers you can often find the grain exchange building. Here sellers and buyers of grain would gather each day to buy, sell, and speculate. Farmers are just one part of working agricultural markets. Weather and harvests are hard to predict. Grain can be stored for some time, though at a cost.

In India and across much of the developing world, governments manage grain storage, and manage it poorly. India’s failed food system (Asianage, December 27, 2017), reports:

India grows enough food to meet the needs of its entire population, yet is unable to feed millions of them, especially women and children. …Twenty-one million metric tonnes of wheat — almost equal to Australia’s production — rots each year due to improper storage. …

The Food Corporation of India (FCI) was set up in 1964 to offer impetus to price support systems, encourage nationwide distribution and maintain sufficient buffer of staples like wheat and rice but has been woefully inadequate to the needs of the country. Around one per cent of GDP gets shaved off annually in the form of food waste. The FCI has neither the warehouse capacity nor the manpower to manage this humongous stockpile of foodgrains. Every year, the government purchases millions of tonnes of grain from farmers for ensuring they get a good price and for use in food subsidy programmes and to maintain an emergency buffer. The cruel truth is that most of it has to be left out in the open, vulnerable to rain and attacks by rodents, or stored in makeshift spaces, covered by tarpaulin sheets, creating high rates of spoilage. …

India’s failed food system (Asianage, December 27, 2017),

Grain prices embody the collective guesses of hundreds or thousands of people about what the future will bring for the supply and demand of grain. Prices change each day as news of events small and large filter to the buyers, sellers, and speculators on the grain exchange.

Steam-powered ships opened vast lands in American and Argentina to supply grain to Europe. And steam-powered railroads allowed Ukraine to become a bread-basket to the world. Transportation costs dropped gradually, then rapidly through the 1800s. Low-priced grain from the Americas “flooded” Europe, leading European landlords, the landed aristocracy, to lobby Parliament for tariffs on imported grain. The aristocracy of the time favored “fair trade” not free trade. Lower grain prices led to lower rents on their farmland.

No one can really see into the future and know what corn, oil, or copper prices will be next week, next month, or next year. No one can know the future, but professional speculators invest time and resources to make educated guesses. When wrong they lose their own money but when correct they earn profits by better coordinating consumer behavior through time. The warning from a Ghost of Famines Future alerts speculators to act today. Consumers who are angry now at rising prices benefit in the future when Scrooge’s warehoused corn is released, easing the shortage and stabilizing or lowering the future’s higher prices. Scrooge profits by coordinating consumption through time.

Yet, interestingly, his actions also generate incentives that can eat away at his potential earnings. By warehousing corn and pushing prices higher now, he not only signals conservation by consumers, but also nearby production and transport from distant lands. Higher than expected prices signal farmers to expand output and bring new land into production. These behavior changes caused now by Scrooge’s purchases and warehouse will take time to bear fruit. So when the future shortage and perhaps even famine arrives some farmers will have expanded production without ever having seen a ghost themselves. Scrooge’s vision and visionary action signal invisibly through higher prices today that high or higher prices are expected in the future.

Such “excess” grain production does not help Scrooge profit, in fact it will lower his potential gains as the expanded harvests come to market. Still, Scrooge could not expect to feed all of London from his warehouse. He will profit enough and his speculating will have spurred production (as well as conservation). And the ghost of possible famine will fade in the face of multiple grain sources. All this happens invisibly through changing prices, contracts, and private property.

Back to Cratchit, Wage Rates, & Responsibility

Many essays have been written on the economics of A Christmas Carol. But some in my opinion hit a sour note by attacking Cratchit as incompetent and painting Scrooge as a hero. We have the luxury of writing our own postscript to the story, one where Scrooge gains friends and continues to run his business profitably. In our free-market postscript, Scrooge can take an active interest both in supporting well-run and effective charities, and in agitating for government to shut down or reform poorly-run poor houses.

After his conversion, Scrooge gives Cratchit a raise, doubling his salary. Does that mean he was just exploiting him earlier or that Cratchit was not particularly competent and now gets charity? No, I think the raise can be seen as reasonable, reflecting Scrooge’s wish to give Cratchit more responsibility at the firm–a result of his chage of heart. Scrooge met his own mortality in his dreams that night. He dreamed himself standing before his own grave. Mortality creeps up quietly on all of us and perhaps more suddenly on busy and successful businessmen. With no board of directors to push for a “succession plan” for the firm of Scrooge & Marley, he had avoided the issue.

Scrooge likely didn’t pay Cratchit more earlier because he hadn’t given him enough responsibility to be worth more. With Scrooge’s change of heart, higher pay would go hand in hand with higher productivity from Cratchit. Scrooge will need to free up time, after all, for board meetings at the various charities he will be asked to join (word of unexpected large donations gets around fast in the nonprofit community). Consider too that giving Cratchit more responsibility and more knowledge of the business could significantly raise Cratchit’s income-earning ability for the firm. Scrooge can make higher profits from a more productive and better-paid Cratchit.

It could be claimed that Cratchit is incompetent, but nothing indicates bad work habits in the story, apart perhaps from showing up late to work one day–but that could be blamed on the overlarge and unexpected turkey Scrooge himself donated the day before. The audience, unfortunately, sees only the seemingly arbitrary nature of pay. Bosses can apparently double someone’s pay if only nightmares scare them half to death (something politicians and labor unions have tried to do ever since).

So yes I recommend George C. Scott’s A Christmas Carol. Maybe it’s not as fun as the Mr. Magoo’s cartoon version, but older students can find economic lessons in the story. From nineteenth century England to the twentieth century developing world, prices, markets, trade, and speculators like Scrooge open doors for human flourishing.

Gregory Rehmke is a writer and economic educator based in Seattle. He is the coauthor (or “with” author) of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Global Economics, and directs Economic Thinking, a program of the nonprofit E Pluribus Unum Films. More information at www.EconomicThinking.org.