Did Ebenezer Scrooge Dream a Better Life for Himself?

(Revised and expanded version of 2004 post, quoted in December 17, 2006 Toronto Star article “The Politics of Ebenezer Scrooge“)

Family, Work, Community

Did Ebenezer Scrooge Dream a Better Life for Himself?

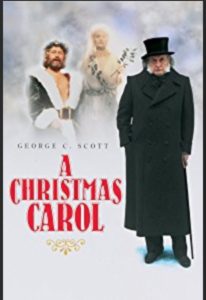

Reflections on watching George C. Scott in Dicken’s “A Christmas Carol”

by Gregory Rehmke

Consider Charles Dicken’s Ebenezer Scrooge, brought to life by George C. Scott in the television movie from the 1990s. George C. Scott plays Scrooge as a competent businessman who finds both Christmas and philanthropy a waste of time and money. His eyes are opened through a series of nightmarish dreams. The book and various movie versions are offered today as indictments of greed and business, as well as celebrations of the joys of family, Christmas, and giving to those less fortunate.

Consider Charles Dicken’s Ebenezer Scrooge, brought to life by George C. Scott in the television movie from the 1990s. George C. Scott plays Scrooge as a competent businessman who finds both Christmas and philanthropy a waste of time and money. His eyes are opened through a series of nightmarish dreams. The book and various movie versions are offered today as indictments of greed and business, as well as celebrations of the joys of family, Christmas, and giving to those less fortunate.

Viewers can look at this classic story through a pro-market lenses and see different lessons than do the majority who misunderstand capitalism and the role of markets and prices. And we can write our own last chapter to the story that lets Scrooge live a happier life without compromising his business principles.

I would argue that a better, though less dramatic, interpretation of the story is simply that people—especially successful businesspeople—can get too wrapped up in their work, and lose touch with the rest of their lives. Engagement in civil society brings many unexpected and hard-to-quantify pleasures. Philanthropy can be satisfying to the giver as well as helpful to the receiver. And even the most anti-business take on “A Christmas Carol” still must admit it is Scrooge’s private philanthropy, not the state, that in the end helps the poor.

The story begins with Scrooge successful in business but having let his personal and social world fade. He long ago let his love relationship drift away and deep down regrets it. After a difficult childhood, he gradually gained a kind of comfort in solitude and emotional isolation. As is usual in novels and movies, nothing positive is said or implied about his work. No glimmer of understanding that he must be providing a valuable service in order to stay in business and make profits. But we can agree that focused businessmen like Scrooge can lose track of their family and social lives and find themselves years later wealthy but alone.

Second, the story features an interesting, if subtle, attack on government welfare. Scrooge is asked to donate to a relief fund. He answers that he pays taxes for just such purposes. Why don’t the homeless go to existing poor houses or to prisons he asks? The private-relief fund-raisers ask him if he has ever seen the government relief houses. Scrooge answers no, he hasn’t. He is responding reasonably and so are they. (Should we expect a socially-responsible Scrooge of today to donate to innovative private charities, or to agitate for repair of failing government welfare programs?)

Tax-supported relief houses give the emotionally-distant Scrooge an excuse not to take personal responsibility for the poor. He has already paid, he claims, through his taxes. He uses government-funded welfare agencies as an excuse to avoid supporting private relief agencies. With no state-run poor houses in England, he might still have said: “Bah, Humbug!” and been tempted to “free-ride” on donations of others. That is, he might free-ride (an economics term) by relying on others to donate to help beggars. Scrooge would benefit from beggar-free streets without spending a dime on donations (he is greedy in the story, after all).

Few of us enjoy seeing and dealing with homeless people begging on the street. Scrooge could well have been drawn into private relief just to keep beggars out of his way. Still a selfish motive, but one that would require helping others in order to help himself. He could have invested in enterprises that create job-expanding opportunities that help the unfortunate or unwise to get back on their feet. Consider too that Scrooge’s current business, speculation, could very well be helping the poor more effectively that any charity he might choose to support (more on this possibility below).

Had Scrooge invested in a job-training firm, for example, he could carry business cards promoting his job-training services to helpfully put in the cups of beggars. In this way he could have helped the needy and profited as an investor in training-services at the same time (perhaps naming his enterprise Scrooge Phoenix University). Many for-profit as well as nonprofit organizations today provide job-training services and generate income through job-placement. The poor learn skills and pay a portion of their later salaries back to the job-training/job-placement organizations.

My great-great-grandfather, Dr. Thomas Guthrie helped start the Ragged Schools for Children in Scotland and England. He went to the Scrooges of his day (the 1840s) and convinced them to contribute. There were 192 Ragged Schools in operation at its peak with 20,000 destitute children attending each year. An estimated 300,000 attended overall, from 1840s to 1880s. The English government apparently saw the Ragged Schools as unwanted competition to their poor houses and new government-funded schools, and they drove the Ragged Schools out of business. (Students apparently preferred the industry-training they received as part of their education at the Ragged Schools. The UK government went so far as to sue to force students out of Ragged Schools and into government schools. Glimpse this fascinating story here: [updated link: http://infed.org/mobi/ragged-schools-and-the-development-of-youth-work-and-informal-education/ )

Because Scrooge feels he has already discharged his obligation to help the poor (thanks to state-mandated poor-house welfare), he loses touch with that part of the world. He doesn’t bother looking into the management and operation of poor houses because their tax-funding insulates them from private reform. And he knows he wouldn’t be allowed to withhold his taxes if he found them badly managed.

Had he been able to choose among private alternatives he would have had an incentive to investigate how his money was used. He doesn’t do much investigation after being saved, in the George C. Scott version. He just gives a big donation to the private relief effort he refused the day before. But even so, he will surely take an acute interest in that private relief project after donating a huge sum to it. He would be angered as well as embarrassed if the relief effort he supported turned out to be ill-managed or a fraud.

Scrooge, thanks to tax-funded poor houses, is less likely to be drawn into civil society philanthropies that might have opened up his life (and he might have been less in need of spiritual shock-therapy).

His very skeptical eye would be a valuable service for private charities, as he seems to understand that good intentions matter less than good results. He would probably be a better trustee of a private charity than his “do-gooder” nephew, for example.

George C. Scott’s Scrooge notes with disapproval his nephew’s offer to overpay Cratchit’s son. Scrooge understands that overpaying for a young person’s first job can have negative consequences. It breaks the connection between a person’s productivity and their pay. It confuses charity with wages in the mind of both the employee and employer.

The intricate dance toward “just” or market wages not only pits each worker against others willing to take on a job, it pits each employer against all others willing to pay higher wages. When employers get greedy and try to hold wages below the marginal earnings each worker brings the firm, other employers have a profit opportunity, if they can hire that worker away.

The push for profits in the labor market leads employers to a bidding war that narrows the gap between what workers earn for firms and what they are paid. Competition for workers is endlessly frustrating for employers who hire and train new employees only to find them lured away by better offers. The core source of Bob Cratchit’s low pay is likely his limited responsibility and productivity at the firm of Scrooge and Marley. In fairness to Mr. Cratchit, it may not be his fault that Scrooge has been holding on too tight and not delegated enough. Marley may have offered Scrooge more opportunities to learn and share responsibilities at the firm than Scrooge had so far given Cratchit. Either could be blamed, but it seems reasonable to find fault with the side most capable of changing the situation: the boss.

Seeing the Ghost of Famine future

For a businessman like Scrooge, such a vision might lead to careful (and costly) review of weather news across Europe as harvests approached. News of potentially bad harvests would be a reasons for taking a major investment position. Early on in the movie George C. Scott’s Scrooge visits the city grain exchange to do some business. He holds out for a higher price for corn in his warehouse, and is accused of hurting the poor through his greed. But is holding out for higher prices really hurting the poor? Yes and no.

His “hoarding” or speculating on grain does raise the price today. But it also has the consequence of pushing prices down in the future. Scrooge has seen a vision of scarcer grain and higher prices in the future (otherwise he would sell at today’s prices). He is raising the price of grain for the poor (and everyone else) today in exchange for lowering the price in the future. If his vision proves true, he will have performed a service for society by pushing all to conserve now a resource that will be more scarce in the future.

The businessmen in the movie claim Scrooge is raising grain prices for the poor today by holding back. These less visionary businessmen may lack the weather information Scrooge could have gathered. Or they may just wish to buy Scrooge’s corn at lower prices either to help the poor today or to help themselves. How can we know they would pass these lower prices on to consumers? Perhaps they would just pocket gains from below-market prices themselves. In any case, raising prices now can in fact help the poor. (How is that for a Scrooge-like claim!)

Speculators like Scrooge are time-shifters. Whether or not inspired by ghostly visions, they trade goods through time. Scrooge fills his warehouse with corn then turns the dial on a time-machine to transport them to the future. It is an expensive and risky enterprise. Who knows what the future will bring? Such businessmen make informed guesses, they speculate about the future. If they are right, their fourth-dimension transportation system earns profits, even after paying rent on warehouse space and interest on money tied-up over time. If they guess wrong they lose their investment. And after too many wrong guesses, both Scrooge and Cratchit would be looking for new work.

Scrooge was neither a landed aristocrat born with a silver spoon, nor a farmer, nor a manufacturer. How did Scrooge happen to have the corn in his warehouse in the first place? Economists argue he is performing a service by warehousing corn and releasing it when demand is strong. In the movie he is presented as being greedy and pushing prices higher, thus hurting the poor. But by aiming to make profits speculating on corn, his early purchase pushes prices slightly up and encourages conservation now. By speculating in corn he is a visionary. He guesses that in the near future, current plentiful corn supplies will turn scarce. Those lulled by relatively low corn prices to use it casually today would regret it later–but by then it would be too late. Only by taking action before the shortage can some of today’s relative plenty be set aside for tomorrow.

No one can really see into the future and know what corn, oil, or copper prices will be next week, next month, or next year. No one can know the future, but professional speculators invest time and resources to make educated guesses. When they are wrong, they lose their own money, but when correct they make money by better coordinating consumer behavior through time. The warning from a Ghost of Famines Future alerts speculators to act today. Consumers angry now at rising prices benefit in the future when Scrooge’s warehoused corn is released, easing the shortage and stabilizing or lowering the future’s higher prices. Scrooge profits by coordinating consumption through time.

Yet, interestingly, his actions also generate incentives that can eat away at his potential earnings. By warehousing corn and pushing prices higher now, he not only signals conservation by consumers, but also new production. Higher than expected prices signal farmers to work to expand output, to bring new land into production. These behavior changes caused now by Scrooge’s purchases and warehouse will take time to bear fruit. So when the future shortage and perhaps famine arrives some farmers will have expanded production without ever having seen a ghost themselves. Scrooge’s vision and visionary action, signal invisibly through higher prices today that high or higher prices are expected in the future.

Such “excess” grain production does not help Scrooge profit, in fact it will lower his potential gains as the expanded harvests come to market. Still, Scrooge could not expect to feed all of London from his warehouse. He will profit enough and his speculating will have spurred production. And the ghost of possible famine will fade away in the face of both grain sources. All this happens invisibly through changing prices, trusted contracts, and private property. (And not only happens invisibly, but stays invisible for 160 years!)

Back to Cratchit, Wage Rates, & Responsibility

After his conversion, Scrooge gives Cratchit a raise, doubling his salary. Does that mean he was just exploiting him earlier? Or that Cratchit was not particularly competent? No, I think the raise can be seen as a very reasonable decision, part of Scrooge’s change of heart, that he wishes to give Cratchit more responsibility at the firm. Scrooge met his own mortality in his dreams that night. He dreamed himself standing before his own grave. Mortality creeps up quietly on all of us, perhaps especially on busy and successful businessmen. With no board of directors to push for a “succession plan” for the firm of Scrooge & Marley, he had avoided the issue.

Scrooge likely didn’t pay more earlier because he hadn’t given Cratchit enough responsibility to enable him to be worth more. With Scrooge’s change of heart, higher pay would go hand in hand with higher productivity from Cratchit, which would follow from additional responsibilities. Scrooge will need to free up time, after all, for board meetings at the various nonprofits he will be asked to join–word of unexpected large donations gets around fast in the nonprofit community.

It could be claimed that Cratchit is incompetent, but nothing indicates bad work habits in the movie, apart perhaps from showing up late to work one day–but that could be blamed on the overlarge and unexpected turkey Scrooge himself donated the day before. The audience, unfortunately, sees only the seemingly arbitrary nature of pay. Bosses can apparently double someone’s pay if only spirits scare them half to death in nightmares (something politicians and labor unions have tried to do ever since).

So I recommend George C. Scott’s A Christmas Carol to my young nieces and nephew. They will enjoy it as will other young people (though perhaps not as much as the Mr. Magoo’s cartoon version). Still the hard part is keeping them attentive for the thirty-minute economics lecture following.

Gregory Rehmke (grehmke@economicthinking.org) is a writer and economic educator based in Seattle. He directs Economic Thinking, a program of the nonprofit E Pluribus Unum Films. More information at www.EconomicThinking.org.