Considering Europe and the European Union

The NCFCA league offers a resolution for reforming or abolishing the European Union. NCFCA members have voted, and if the European Union resolution is chosen, it will be announced at the national tournament. Emmanuel Macron, the French President, has also called for reform, advocating a two-speed or multi-speed European Union.

This July, the Grand Final motion for the 2018 Heart of Europe tournament takes on this proposal:

This House supports a multi-speed Europe.

Also called “two-track Europe” or “variable geometry Europe”, it is the idea that different parts of the European Union should integrate at different levels and pace depending on the political situation in each individual country. In the face of Brexit and many disagreements about how to address the refugee crisis, should some version of this approach become the main direction for the European Union into the future, or is it a better strategy to continue on the course toward full or near-full integration of all EU members?

American Logos debaters headed for the Heart of Europe World Schools tournament are reviewing multi-speed Europe pros and cons. Market advocates call for expanding economic freedom across Europe. Layers of local, state, and E.U. regulations make it complex and time-consuming for entrepreneurs to start and expand enterprises. Licensing restrictions coupled with welfare-state programs deepen dependency and alienation, especially among recent immigrants and refugees. And all this feeds growing radicalism, populism, and nationalism.

On the positive side, Europe has finally mostly recovered from the deep financial meltdown of ten years ago. Brexit, the British exit from the E.U., won with votes from many unhappy with E.U. taxes and regulations plus from many unhappy with new immigrants and refugees. The vote was close but the Brexit win was a shock to U.K. and E.U. establishment. And recent vote in Italy bringing populists to power have raised fears and uncertainty there too.

High taxes added to business and labor regulations have long been a challenge for business in Europe. But the flip side are the various benefits extensive government programs offer, including state health care, welfare, and college education.

Many in the U.K. want the benefits of open trade and investment without the detailed E.U. regulatory burden. Norway and Switzerland trade with E.U. countries and flourish without being in the European Union.

Within the European Union is the Eurozone, made up of countries with the Euro as a common currency managed by the European Central Bank (England kept its own currency and central bank).

Could there be free trade, investment, and migration across European Union countries but without a common European currency and central bank? Whether a centralized fiat currency like the Euro was a good or bad thing for E.U. members turns on whether national monetary authorities would do a better or worse job of managing a national currency. (Often the answer is a that state politicians under pressure from local businesses, unions, and government workers would expand the money supply even more, increasing inflation.)

(An earlier post, Repair, Reform, or Abolish the European Union? discussed E.U. history and economics issues.)

Consider the struggle Uber has had across Europe. Established taxi companies lobby for regulations to block Uber and other “gig-economy” services. This raises costs and reduces choices for everyday people (see, for example Uber to face stricter EU regulation after ECJ rules it is transport firm, The Guardian, December 20, 2017, and from 2015, French taxi drivers lock down Paris in huge anti-Uber protest (The Verge, June 25, 2015) And Amsterdam, other EU cities, urge Brussels to take action on Airbnb data, (DutchNews.nl, January 26, 2018).

Established firms and industry associations across Europe, the United States, and everywhere else regularly lobby local, regional, state, and federal governments for protection against competitors.

The Force Behind Europe’s Populist Tide: Frustrated Young Adults (Wall Street Journal, June 17,2018) is subtitled: “Still struggling to find jobs, and often living at home, younger generations are propelling antiestablishment parties to new heights of power.” . The weight of regulations reduces opportunities for young people and some then turn to populist parties in their opposition to the crony capitalist status quo. Socialists can blame capitalism (or what they think is capitalism), and pro-market people can state bureaucracies, elites whose jobs are secure behind licensing laws.

Consider Greek Business In Action: The Athens Bookstore And Cafe That Can’t Serve Coffee Or Sell Books (Business Insider, February 28, 2012) quoting from economist Megan Greene:

A friend and I met up at a new bookstore and café in the centre of town, which has only been open for a month. The establishment is in the center of an area filled with bars, and the owner decided the neighborhood could use a place for people to convene and talk without having to drink alcohol and listen to loud music. After we sat down, we asked the waitress for a coffee. She thanked us for our order and immediately turned and walked out the front door. My friend explained that the owner of the bookstore/café couldn’t get a license to provide coffee. She had tried to just buy a coffee machine and give the coffee away for free, thinking that lingering patrons would boost book sales. However, giving away coffee was illegal as well. Instead, the owner had to strike a deal with a bar across the street, whereby they make the coffee and the waitress spends all day shuttling between the bar and the bookstore/café. My friend also explained to me that books could not be purchased at the bookstore, as it was after 18h and it is illegal to sell books in Greece beyond that hour. I was in a bookstore/café that could neither sell books nor make coffee.

E.U. countries can increase labor regulations, but not reduce them below central E.U. mandates, according to this European Commission: EMPLOYMENT, SOCIAL AFFAIRS & INCLUSION page:

Individual EU countries are free to provide higher levels of protection if they so wish. While the European Working Time Directive entitles workers to 20 days’ annual paid leave, for example, many countries have opted for a more generous right to the benefit of workers.

So for the Greek coffee shop/bookstore owner who must pay employees to walk to another store and buy coffee, the E.U.Working Conditions – Working Time Directive requires:

• a limit to weekly working hours, which must not exceed 48 hours on average, including any overtime

• a minimum daily rest period of 11 consecutive hours in every 24

• a rest break during working hours if the worker is on duty for longer than 6 hours

• a minimum weekly rest period of 24 uninterrupted hours for each 7-day period, in addition to the 11 hours’ daily rest

• paid annual leave of at least 4 weeks per year …

We can all wish for higher wages and better working conditions. But such wishes face realities with entrepreneurs and business owners facing uncertainty when starting or expanding enterprises. Providing employees four weeks of paid leave requires paying someone else to do that work during those four weeks. And that reduces the wages businesses are willing to offer employees. State and E.U. regulations can try to improve worker welfare by mandating minimum wages, vacations, pensions, and other benefits. But they can’t mandate the financial health firms require to earn enough income to provide these benefits.

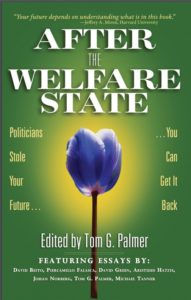

History offers examples of rapidly increasing employment, wages, and profits in Italy and Greece before they adopted labor regulations and welfare state benefits. Two short essays in the Atlas Network collection, After the Welfare State (online pdf here) tell this history in: How the Welfare State Sank the Italian Dream and Greece as a Precautionary Tale of the Welfare State. It’s hard to believe now, but for years, even decades, the Greek and Italian economies grew fasted than either the U.S. or West Germany.

From How the Welfare State Sank the Italian Dream:

From 1946 to 1962 the Italian economy grew at an average annual rate of 7.7 percent, a brilliant performance that continued almost until the end of the ’60s (the average growth over the whole decade was 5 percent). The so-called Miracolo Economico turned Italy into a modern and dynamic society, boasting firms able to compete on a global scale in any sector, from washing machines and refrigerators to precision mechanical components, from the food sector to the film industry.

The period 1956 to 1965 saw remarkable industrial growth in Western Germany (70 percent in the decade), France (58 percent) and the United States (46 percent), but all were dwarfed by Italy’s spectacular performance (102 percent). Major firms, such as the auto-maker Fiat; the typewriter, printer, and computer manufacturer Olivetti; and the energy companies Eni and Edison, among others, cooperated with an enormous mass of small fi rms, many managed by families, in accordance with the traditionally strong role of the family in Italian society. (pages 15-16)

And, from Greece as a Precautionary Tale of the Welfare State:

Modern Greece has become a symbol of economic and political bankruptcy, a natural experiment in institutional failure. It’s not easy for a single country to serve as a textbook example of so many institutional deficiencies, rigidities, and distortions, yet the Greek government has managed it. The case of Greece is a precautionary tale for all others.

Greece used to be considered something of a success story. One could even argue that Greece was a major success story for several decades. Greece’s average rate of growth for half a century (1929–1980) was 5.2 percent; during the same period Japan grew at only 4.9 percent.

These numbers are more impressive if you take into consideration that the political situation in Greece during these years was anything but normal. From 1929 to 1936 the political situation was anomalous with coups, heated political strife, short-lived dictatorships, and a struggle to assimilate more than 1.5 million refugees from Asia Minor (about one-third of Greece’s population at the time). From 1936 to 1940 Greece had a rightist dictatorship with many similarities to the other European dictatorships of the time and during World War II (1940–1944) Greece was among the most devastated nations in terms of percentage of human casualties. (Pages 21-22)

There is much more in these two short After the Welfare State chapters and they recount what when wrong when Greek and Italian politicians adopted policies that gradually reduced enterprise and innovation across once dynamic economies.

Diverse Europe offers more relevant examples with the fiscal stability and economic dynamism of northern European economies. This pre-Brexit Economist article profiles: The new Hanseatic League: Britain excavates an old alliance in Europe’s liberal, free-trading north (The Economist, November 30, 2013)

The mercantile spirit lives on, too: Britain, Germany, the Netherlands, the Nordics and the Baltics share a taste for balanced books and free trade. Most underwent economic reforms before the euro-zone crisis and have low bond yields and triple-A credit ratings to show for it. Many sport prominent Eurosceptic parties such as the True Finns, Alternative for Germany and the UK Independence Party, which channel voters’ anger at being yoked to Europe’s languid, unreformed south.

The kinship is not lost on British politicians. In January David Cameron, the prime minister, gave a speech in London (near the site of the trading post, as it happens) in which he pledged to overhaul Britain’s EU membership and, if re-elected with a majority in 2015, put the result to an in-out referendum. He pleased northern allies by sketching a vision of a leaner, more competitive Europe in the interests of “the entrepreneur in the Netherlands, the worker in Germany, the family in Britain”. The EU should spend less and concentrate on trade-boosting measures, he argued.

This has spurred excited talk in Westminster of a northern alliance—a new Hanseatic League, as it were. The British government’s review of the balance of powers between Brussels and London has attracted widespread interest abroad, note diplomats. Separately, the Dutch held their own review, which concluded that Europe should integrate less and liberalise more; music to British ears. And a template for an alliance already exists: since 2011, Mr Cameron has convened an annual “Northern Future Forum” of Nordic and Baltic states.

Concluding back in Italy, here are two articles from Alberto Mingardi head of the Bruno Leoni Institute, the first from early 2017: Europe’s problem is not populism: What the Continent needs is to restart growth (Politico, January 4, 2017) and from 2018: Italian voters head for euro showdown: Italians are angry at the establishment, but are afraid of impending financial disaster..