Catalonia a Nation or Barcelona a City-State?

The NSDA Public Forum topic for January: “Resolved: Spain should grant Catalonia its independence,” opens students to a range of complicated politics, economics, and history. The 2020 NCFCA topic on E.U. immigration reform also offers an opportunity to revisit Europe’s long tradition of city-states and decentralized governance.

In history classes students tend to learn (and maybe memorize) the many countries and past wars of Europe. But many European (and African) states are relatively recent. Turmoil in Libya, Syria, and Iraq partly reflects the artificial nature of these countries, shaped by colonial powers only after World War I.

What Is a Nation in the 21st Century?, (New York Times, Oct. 27, 2017), asks questions and provides background on events leading up to the campaign and vote on Catalonia independence from Spain:

The recent independence referendums in Iraqi Kurdistan and Catalonia, and the predictable heavy-handed responses from the central governments in Baghdad and Madrid, have raised many questions — a catechism without answers — on the meaning of nationhood in the 21st century. What is a nation? What is a nation-state? Is it the same as a country? Are a people, or a tribe, the same thing as a nation? In a globalized economy what does national sovereignty really mean?

Catalonia has a history stretching back centuries. Similarly, Provence, in the south of France, was a semi-independent state with it’s own language until 1486 when it’s “title” passed to the King of France. Students caught speaking Provençal were beaten as formal French was enforced.

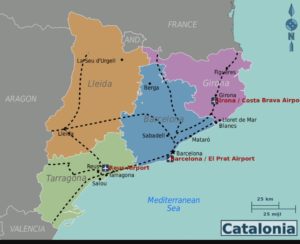

The Catalonia region with the dynamic city of Barcelona is an economic powerhouse note the author of “Catalan Independence And The Revival Of City-States,” (Daily Kos, Sept. 22, 2017)

Barcelona and its environs account for a significant portion of Spain’s economy, about 20% of Spanish GDP in 2013, and Catalans have been increasingly unhappy with essentially subsidizing the rest of the country. That was exacerbated in 2012 when the Spanish government rejected a plan to negotiate Catalonia’s demand for a better fiscal agreement for the region.

BBC News, in “Catalonia’s bid for independence from Spain explained,” (Dec. 22, 2017), review recent politics, then looks at Catalonia’s claim to be a nation:

It is certainly long-lived. It has its own language and distinctive traditions, and a population nearly as big as Switzerland’s (7.5 million).

It is also a vital part of the Spanish state, locked in since the 15th Century, and – according to supporters of independence – subjected periodically to repressive campaigns to make it “more Spanish”.

https://goo.gl/images/PtyVtj

European countries have a complex history as can been seen by looking at the changing shapes and names of countries over the last 500 years. Here is a map from 1600:

NCFCA Lincoln-Douglas students face similar challenges with their nationalism/globalism topic. Earlier posts have emphasized federalism and limited government as a Constitutional alternative to either more nationalism or globalism (and of course defining either term is a challenge). Economists argue that global trade and investment create wealth, but national as well as global bureaucracies can distort trade and investment.

The advantages of local governance by an independent Catalonia or Kurdistan can be outweighed by new trade barriers and restrictions on investment and migration. (Plus new business regulations from newly empowered legislature and bureaucracies.)

Global and regional institutions like the United Nations, World Bank, IMF, NAFTA, European Union, or the Bank for International Settlements derive their authority from associations of nation-states, but can be corrupted by corporations, NGOs, and other special interests.

For an alternative for addressing global issues look to city-states of the present, future ,and past. This Aeon essay, Return of the city-state, gives students a tour of of western civilization after the Roman Empire and before the rise of nation-states:

We are just as deluded that our model of living in ‘countries’ is inevitable and eternal. Yes, there are dictatorships and democracies, but the whole world is made up of nation-states. This means a blend of ‘nation’ (people with common attributes and characteristics) and ‘state’ (an organised political system with sovereignty over a defined space, with borders agreed by other nation-states). Try to imagine a world without countries – you can’t. Our sense of who we are, our loyalties, our rights and obligations, are bound up in them.

The essay continues:

Until the mid-19th century, most of the world was a sprawl of empires, unclaimed land, city-states and principalities, which travellers crossed without checks or passports. As industrialisation made societies more complex, large centralised bureaucracies grew up to manage them. Those governments best able to unify their regions, store records, and coordinate action (especially war) grew more powerful vis-à-vis their neighbours.

The explanation given for the rise of nation-states (that “large centralised bureaucracies grew up to manage them”) is misleading. Economic historians would argue instead that rule of law institutions that protected property rights and allowed new enterprises to develop grew wealthy. Expanding government bureaucracies often smothered or distorted new enterprises and restricted international trade. See Angus Deaton’s The Great Escape, or Daron Acemoglu’s Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty , and especially the earlier North and Thomas, The Rise of the Western World: A New Economic History. “Large centralized bureaucracies” have been more the problem than the solution.

For more on the history of Charter Cities and economic development see “The Politically Incorrect Guide to Ending Poverty,” (The Atlantic, July/August 2010). Also “China to Palestine: Let Charter Cities & Economic Freedom Bloom,” was written for a NSDA topic last year (March 7, 2017)

Also see, The Spanish Court Decision That Sparked the Modern Catalan Independence Movement , (The Atlantic, October 1, 2017) and in Foreign Policy, Catalonia’s Crisis Is Just Getting Started, December 27, 2017:

…the conflict has much deeper roots, and its main trigger was the failed process to expand Catalonia’s autonomy a decade ago. During the discussion of the new autonomy law in mid-2000s, Rajoy’s People’s Party launched a strong campaign against the law that led to the boycott of Catalan products, infuriating most Catalans.