Alabama’s Private Property in the Ocean Policy

Researching marine natural resource policies for an Economic Thinking workshop in Huntsville, I surfed into Alabama’s entrepreneurial artificial reef program. Alabama’s limited coastline is listed as just 53 miles, except on the Encyclopedia of Alabama website, where “Alabama’s shoreline along the Gulf of Mexico stretches for 60 miles.” This website notes that Alabama beaches attract tourists and provides “more than 50,000 jobs and generates more than $2 billion in revenue annually.” And the shape of the shoreline with coastal bays and rivers “extends another 600 miles.”

Researching marine natural resource policies for an Economic Thinking workshop in Huntsville, I surfed into Alabama’s entrepreneurial artificial reef program. Alabama’s limited coastline is listed as just 53 miles, except on the Encyclopedia of Alabama website, where “Alabama’s shoreline along the Gulf of Mexico stretches for 60 miles.” This website notes that Alabama beaches attract tourists and provides “more than 50,000 jobs and generates more than $2 billion in revenue annually.” And the shape of the shoreline with coastal bays and rivers “extends another 600 miles.”

Tourists traveling to the Alabama coast are drawn by more than white sandy beaches. Many come for offshore fishing, and much of that fishing is around 17,000 artificial reefs (95% build by the private reef builders). Gulfshores.com explains:

Since the 1950s, Alabamians have been building artificial reefs because Alabama was one of the have-not states for natural reefs. Although Alabama had some rock and coral formations, for the most part, there was very little bottom reef to attract and hold marine life and large populations of fish. However, the Alabama Marine Resources Division, area charter boat captains, private boat owners, and conservation organizations then began an effort to build reefs to attract fish.

Today, Alabama has created the largest artificial reef program in the United States with over 17,000 artificial reefs. The makeup of these reefs includes tanks, barges, bridge rubble, and all matter of reef material. But, the majority of the reefs are sunk in extremely deep water well away from shore. (Source.)

Michael De Allessi, in a 1996 study, Private Reef Building in Alabama and Florida discusses the history of private fishing reefs and the 1984 federal legislation that opened the door to artificial reefs along U.S. coastlines. Alabama and Florida charted a different path to develop artificial reefs along their coastlines:

Throughout much of the U.S., artificial reefs are created directly by state conservation departments. Alabama and Florida are two exceptions: They began to tap the connection between ownership and stewardship by creating limited areas where private groups and individuals could create their own reefs. Once the reefs are in the water they become public property, but the exclusive knowledge of where reefs are located allows their “owners” to benefit from the productivity of the reefs and discourages them from overfishing. Of course, this ownership only lasts as long as the reef location remains a secret, but even this fleeting property right has resulted in a tremendous private initiative to enhance the marine environment in these two states. (Source.)

De Allessi’s study was published over 15 years ago, so it is fascinating to see how Alabama’s artificial reef industry has expanded since. Alabama provides a way around complex federal regulations of artificial reefs with 1,200 square miles of offshore waters open to “reef entrepreneurs” who can get a permit in one

day for $25. The artificial reef’s location is not published, which is key because the private reef developer will bring customers to the site later to fish or dive.

Most of the ocean floor off the Alabama coast is barren, but artificial reefs quickly fill with with aquatic life.

Earlier posts on artificial reefs are here and here, but the scale of private sector reef building in Alabama waters is far more extensive, and could be a model for other states and new federal reef reforms. Reform could open tens of thousands of additional square miles of ocean floor for offshore reefs developed and managed by fishing enthusiasts, charter boat captains, aquariums, and non-profit ocean-protection groups.

De Allessi discusses the kinds of cooperation between charter boat captains for fishing artificial reefs. One example:

In Alabama, the permit areas are large, the permitting process is liberal, and a large number of reefs exist. There, the only cooperation is among smaller groups like the 22 boats that dock at Zeke’s Marina. These boats make up Zeke’s Charter Fleet Association, a private group that enforces the rule that to keep a boat at Zeke’s Marina, a boat owner must agree to create at least ten new artificial reefs every year.

Hurricanes can bury these reefs with sand, and older reefs are quickly fished out as more boats discover their location. With the demand for new reefs to attract new fish unquenchable, private reef-building firms have expanded. Reefmaker “is the largest reef builder in the United States. The Reefmaker has deployed over 35,000 artificial reefs and owns four patents.”

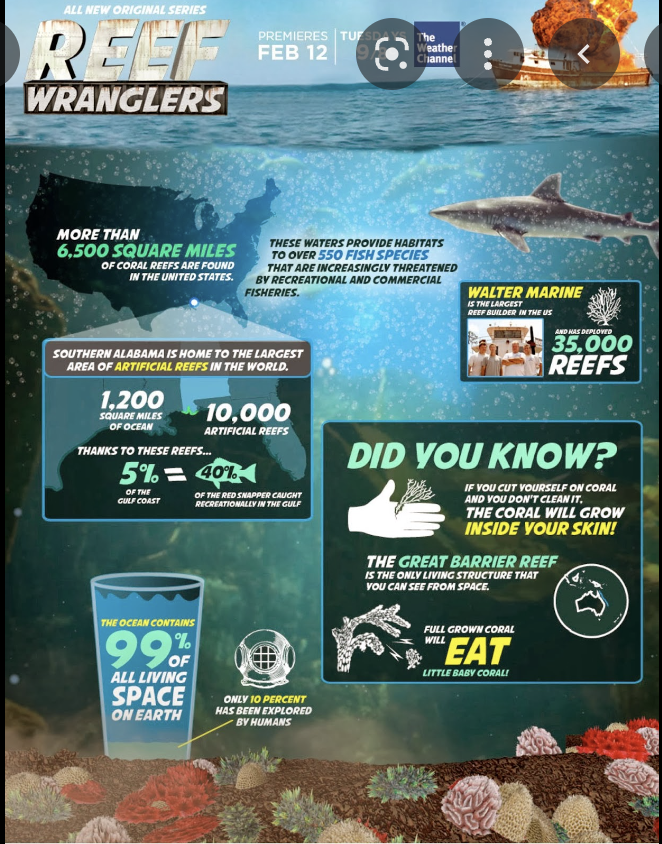

The Weather Channel has jumped onboard the booming artificial reef business with its reality series “Reef Wranglers” based on Walter Marine in Orange Beach, Alabama.Of particular interest is the success story from artificial reefs dramatically increasing the red snapper fishery, shown in a Reef Wranglers poster. With just 5% of the Gulf Coast, recreational fishermen in Alabama waters reel in 40% of red snappers caught in the gulf. New reefs are new homes for red snapper and other marine natural resources.

The full Reef Wranglers poster is below.

Perhaps the most productive artificial reef would be one made of Army Core of Engineers regulations and bureaucracies. You can read the plan here. You can get a sense of the problem of federal bureaucracy from the number of federal agencies involved. There is an artificial reef role for six different federal agencies.

Here is some text from the document:

The Act designates the Secretaries of Commerce and the Army with lead responsibilities to encourage, regulate, and monitor development of artificial reefs in the navigable waters and waters overlying the outer continental shelf of the United States. The Secretary of Commerce is responsible for the Plan, which provides guidance on reef development. Under the Act, the Secretary of the Army, when issuing a permit for artificial reefs, shall consult with and consider the views of appropriate local, state, and federal agencies and other interested parties; ensure that the provisions for siting, constructing, monitoring, and managing artificial reefs are consistent with established criteria and standards;

An page in Outdoor Alabama explains the advantages of siting an artificial reef on state “federal regulation free zones”:

In order for individuals to construct artificial reefs outside of the general permit areas previously mentioned, a permit must be obtained from the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers pursuant to Section 10 of the River and Harbor Act of 1899, Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, and Section 103 of the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act of 1972, as amended.The advantages to utilizing the General Permit Areas for artificial reef construction are numerous, however, the three main advantages are: (A) a permit can be acquired … within one (1) working day…. (B) While the specific area on which an individuals’ artificial reef is not classified, the location is not publicized, and (C) the chances of artificial reefs within the general permit area coming in conflict with other users are reduced. …

It seems reasonable to lease offshore ocean floor for artificial reefs in much the same way as oil and gas exploration sites are leased. Let private firms own and manage fishing and diving over their artificial reef just as oil companies claim ownership of oil discovered under leased Gulf of Mexico tracts of ocean floor.